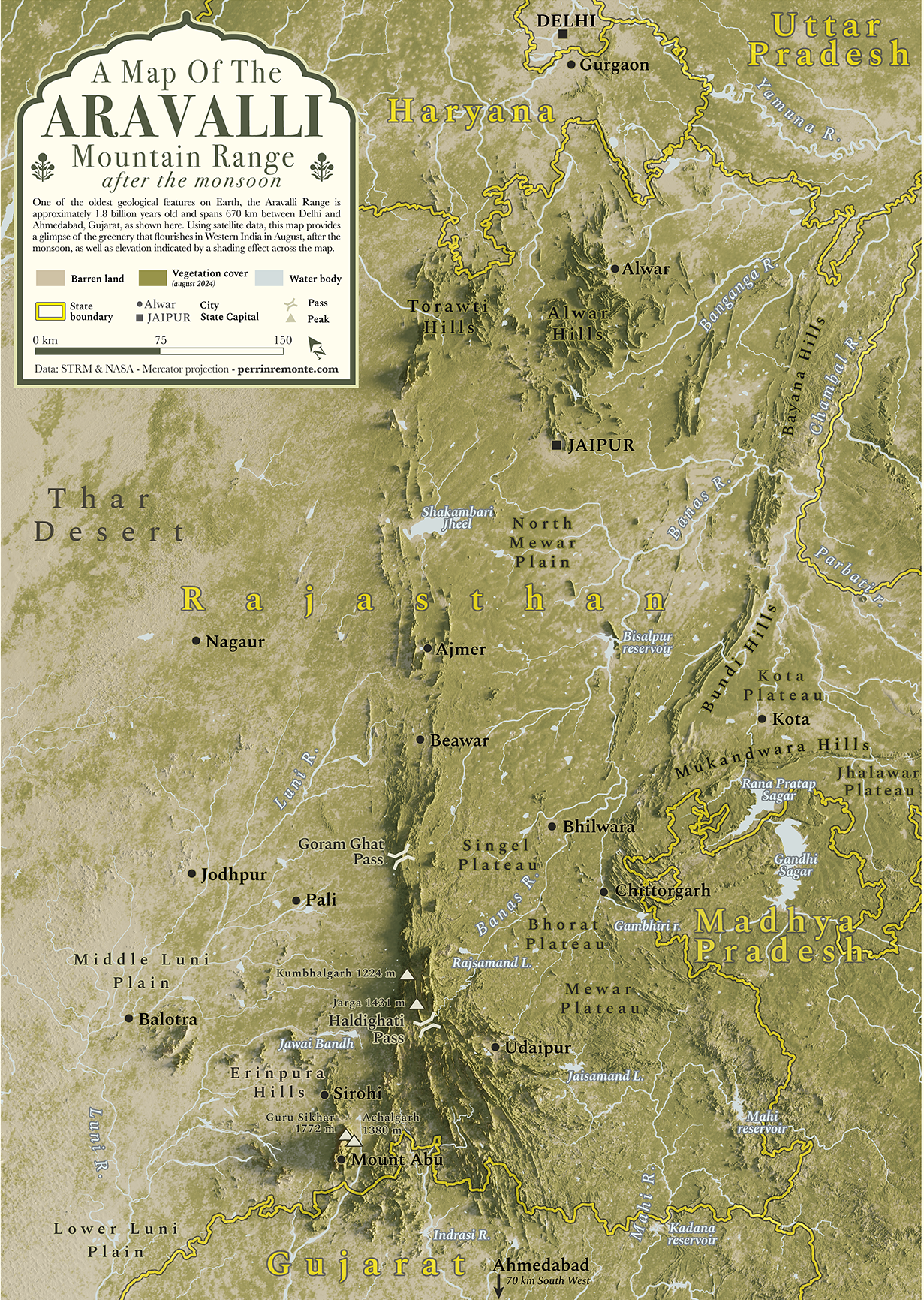

Few natural features in India sit at the intersection of ecology, law and development as sharply as the Aravalli Range. Stretching roughly 800 km from Delhi through Haryana and Rajasthan into Gujarat, the Aravallis are among the oldest mountain systems in the world. Their age, however, has not translated into protection. Instead, the range has become a testing ground for how India balances economic pressure with environmental limits.

The current debate is not merely about mining or definitions; it is about how narrowly or expansively we interpret our ecological responsibilities.

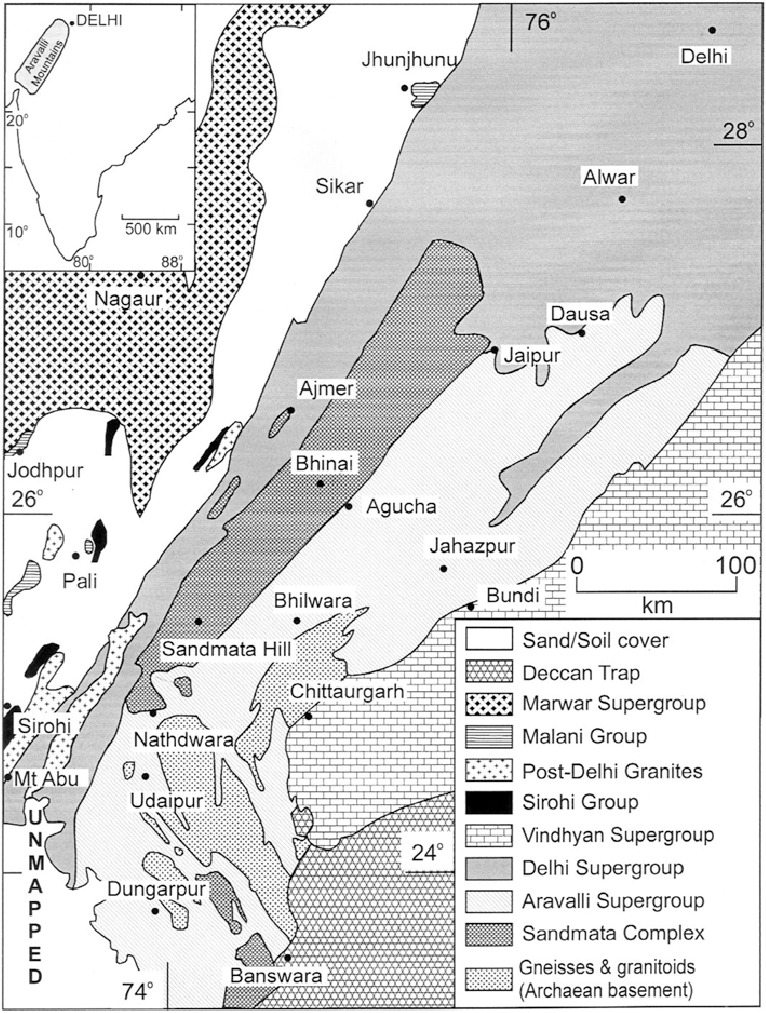

A landscape with a long memory

Geographically, the Aravallis are low, discontinuous hills and rocky outcrops rather than dramatic peaks. Ecologically, they punch far above their height. The range acts as a natural barrier against desertification from the Thar, supports groundwater recharge, moderates regional climate, and hosts dry deciduous forests and wildlife corridors that extend into the National Capital Region. Historically, these hills shaped settlement patterns, trade routes and water systems across north-western India.

Yet their “low height” has also made them administratively vulnerable. Over decades, mining, real estate expansion and infrastructure projects have fragmented large portions of the range, particularly in Haryana and Rajasthan.

What the Supreme Court has said

The latest intervention by the Supreme Court of India reflects this tension. In earlier proceedings, the Court had examined whether only hill formations above a specific height should qualify as “Aravalli hills” for regulatory purposes. Environmental groups argued that such a definition ignores the geological continuity of the range and opens the door to selective exploitation.

Recognising these concerns, the Court has recently paused the implementation of a narrow definition and constituted a new expert committee to re-examine what should legitimately be treated as part of the Aravalli system. Importantly, fresh mining permissions in the region remain restricted while this review is underway. This pause is significant: it signals judicial caution in a matter where irreversible damage is a real risk.

The role of people’s voices

What stands out in this episode is the role of sustained public pressure. Citizen groups, environmental organisations, planners and scientists have repeatedly flagged how incremental legal changes can hollow out protections without formally dismantling them. The debate has shown that environmental governance today is no longer confined to courtrooms and ministries; it is shaped by public scrutiny, data-driven advocacy and professional engagement.

Environmentalists have consistently argued that the Aravallis should be seen as a living ecological system rather than a collection of isolated hills. Urban planners warn that continued degradation will worsen air pollution, water stress and heat extremes in already vulnerable cities such as Delhi, Gurugram and Faridabad.

What lies ahead

The future of the Aravallis will depend heavily on the committee’s recommendations and how firmly the Court enforces them. A science-based, landscape-level definition could strengthen conservation across state boundaries. A narrow, technical approach may offer short-term administrative clarity but long-term ecological loss.

From a professional perspective, this moment demands restraint and foresight. Development is not inherently incompatible with conservation, but redefining nature to suit development is a dangerous precedent. The Aravalli debate is ultimately about choice: whether India treats its oldest mountains as expendable land banks or as essential infrastructure for environmental security. The Supreme Court’s next steps will indicate which path the country is prepared to take.

Also Read: Centre Announces Comprehensive Protection for Entire Aravalli Range; New Mining Leases Banned