In India, monuments are not silent artefacts of the past. They are living structures—worshipped, inhabited, repaired, altered, and often misunderstood. At a time when heritage conservation is increasingly shaped by modern engineering codes and colonial-era frameworks, a crucial question arises: Can India protect its architectural legacy without understanding the indigenous knowledge systems that created it?

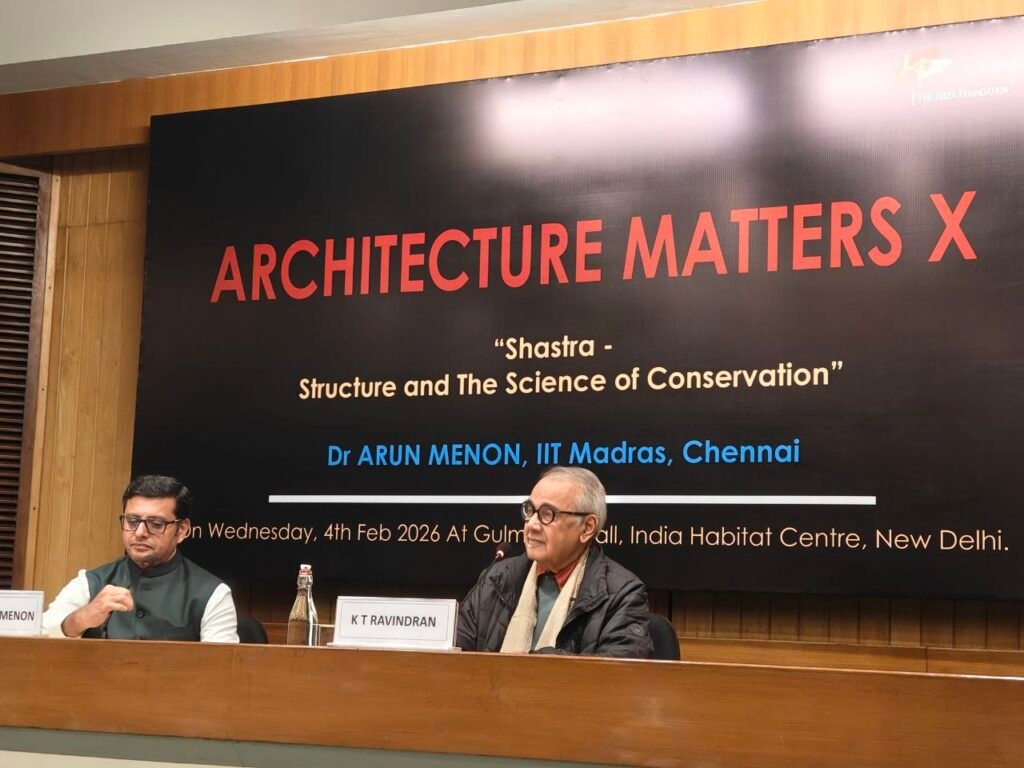

This question lay at the heart of Architecture Matters X, a public panel discussion titled “Shastra: Structure and the Science of Conservation”, organised by the Raza Foundation at the India Habitat Centre. Curated by architect and academic K. T. Ravindran, the session brought together architecture, engineering, history, and traditional practice—fields that rarely meet on equal terms.

The event formed part of the Architecture Matters series, a two-year initiative by the Raza Foundation examining overlooked dimensions of architecture. Conceived alongside “Art Matters,” “Gandhi Matters,” and “Literature Matters,” the series reflects founder Syed Haider Raza’s vision of fostering cross-disciplinary dialogue between the arts, ideas, and public life.

Art Without Science Is Nothing

The keynote address was delivered by Dr. Arun Menon, Professor of Structural Engineering at IIT Madras and Coordinator of the National Centre for Safety of Heritage Structures. Trained originally as an architect and later as an earthquake engineer in Italy, Menon occupies a rare interdisciplinary space—one that allows him to speak fluently across both structural science and cultural meaning. He serves on expert committees advising UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Bagan (Myanmar) and Laos, and has contributed to conservation efforts at Rashtrapati Bhavan, IIM Ahmedabad, the Konark Sun Temple, and Bhutan’s Tango Monastery.

Opening with the medieval maxim “Ars sine scientia nihil est”—art without science is nothing—Menon traced the long-standing tension between artistic interpretation and scientific intervention in heritage conservation. Modern conservation bodies such as ICOMOS and its scientific committee ISCARSA, he noted, recognise that safeguarding monuments requires both cultural sensitivity and rigorous engineering analysis. Structural engineering, when applied thoughtfully, does not threaten heritage values; it enables their survival.

India, however, faces a distinct challenge. Many of its monuments are not archaeological ruins but living temples—active institutions embedded in ritual cycles and public devotion. Conservation decisions, therefore, must answer to both data and devotion.

Listening to Buildings Before Repairing Them

Menon illustrated this principle through a series of conservation projects, beginning with the Jagannath Temple at Puri. A cracked stone beam in the temple’s Natya Mandapa had previously triggered panic-driven responses, including intrusive steel supports that compromised sacred sightlines. This time, however, the approach was different.

Instead of rushing to reinforce, engineers installed crack meters and tilt sensors and monitored the structure over five years. The data revealed that the crack expanded and contracted with seasonal temperature changes but consistently returned to its original position. The conclusion was clear: the beam was stable. When intervention was finally undertaken, it was minimal and visually discreet.

The lesson was unmistakable: heritage structures must be studied as living systems, not frozen ruins. Fear-based repairs can be more damaging than the cracks they seek to fix.

Fire, Forensics, and the Value of Patience

A more dramatic case emerged at the Madurai Meenakshi Temple, where a devastating fire in 2018 gutted a 500-year-old mandapa. The blaze burned for five and a half hours, cracking beams, collapsing slabs, and even melting granite surfaces. Initial reactions called for complete demolition and reconstruction.

Instead, a multidisciplinary team undertook forensic material studies, including microscopic analysis of granite samples. The findings were decisive. Only portions of the structure had reached temperatures high enough to alter the stone’s internal chemistry; the remainder was structurally sound. Armed with scientific evidence, the team convinced authorities to preserve nearly 50 per cent of the original fabric—preventing an irreversible loss of authenticity.

When Modern Materials Become the Problem

At Rashtrapati Bhavan, Menon’s team confronted corrosion in massive cantilevered sunshades that appear stone-like but were constructed using early reinforced concrete. Archival drawings revealed a critical flaw: steel reinforcement embedded in lime concrete—a combination inherently vulnerable to moisture.

Lime concrete’s porosity allowed moisture to corrode the embedded steel. Delamination mapping showed that, in some segments, over 80 per cent of the concrete cover had detached—effectively debris waiting to fall.

Through structural testing, drone surveys, and load experiments, engineers demonstrated that the sunshades were unsafe. The final solution involved controlled reconstruction using compatible materials while preserving the building’s architectural expression. The episode underscored a vital truth: heritage failure is often the result of material incompatibility, not age.

Rediscovering Shastra Through Conservation

Perhaps the most philosophically significant project discussed was the restoration of the Sri Abathsahayeswarar Temple at Thukkachi near Kumbakonam, a 12th-century Chola-era shrine abandoned for decades. Here, conservation required more than engineering—it demanded engagement with Vastu Shastra and traditional temple mathematics.

Working alongside Sthapathis (traditional master builders), Menon’s team reverse-engineered the temple’s proportions using Aayadhi Ganitam, a system in which a single auspicious number governs the dimensions of the entire structure. Derived from human proportions, local grains, astronomical associations, and directional influences, the Aayadhi is not symbolic—it is operational.

By reconstructing this numerical logic, the team ensured that repairs respected not just the temple’s form but its underlying cosmology. The temple was reconsecrated in 2025, restoring both structural integrity and ritual continuity.

Completing the Unfinished Without Guesswork

In another rare conservation decision, the team approved the completion of an unfinished Rajagopuram at the Pundarikatcha Perumal Temple in Tiruvallarai near Srirangam—nearly seven centuries after construction began. Structural simulations, material testing, and textual analysis confirmed that the original design intended a seven-tiered gateway. After multidisciplinary review, completion was approved using traditional methods verified through modern engineering proof checks. Construction is now underway, with consecration expected in 2028.

Towards an Indian Conservation Ethic

India cannot preserve its heritage using imported conservation models alone. Colonial approaches often treat monuments as static objects, disconnected from living traditions. At the same time, restoration without scientific verification can compromise safety and durability.

The way forward lies in dialogue—between engineers and Sthapathis, science and Shastra, law and ritual practice.

As Dr. Arun Menon concluded, conservation is not about freezing buildings in time. It is about helping them endure—structurally sound, culturally alive, and spiritually relevant. India’s traditional knowledge systems are not obstacles to modern science; when used responsibly, they are vital partners in safeguarding living heritage.

Debating the Sacred and the Structural

The discussion that followed highlighted the complexity of working at the intersection of faith, science, and accountability. Audience members raised questions about resistance from temple authorities, regional variations in Shastric traditions, fire safety in historic temples, and the compatibility of metaphysical elements with modern structural verification.

Responding candidly, Dr. Menon acknowledged that tensions do arise—particularly when modern materials such as reinforced concrete conflict with Agamic prescriptions. However, he emphasised that dialogue, multidisciplinary consultation, and evidence-based analysis have consistently helped resolve such conflicts. While Shastric systems include metaphysical dimensions, conservation decisions must ultimately withstand legal and structural scrutiny.

The exchange reinforced a central theme of the evening: heritage conservation in India is neither purely technical nor purely ritualistic—it is a negotiated process requiring patience, scholarship, and professional responsibility.

Also Read: Architecture Matters IX: Exploring the City Through Words, Horizons, and Human Experience