(Source: https://www.southindiatoursandtravels.com/)

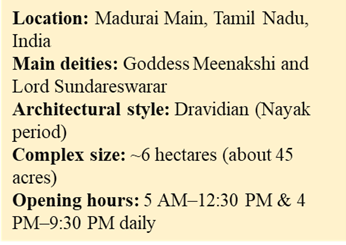

In the heart of Madurai, Tamil Nadu, the Meenakshi Amman Temple stands as an enduring testament to the union of sacred design, Vastu principles, and structural genius. Built primarily under the Nayak rulers in the 16th–17th centuries, the temple’s architecture has not only drawn pilgrims and tourists but also engineers and planners seeking insight into ancient construction systems that rival modern techniques.

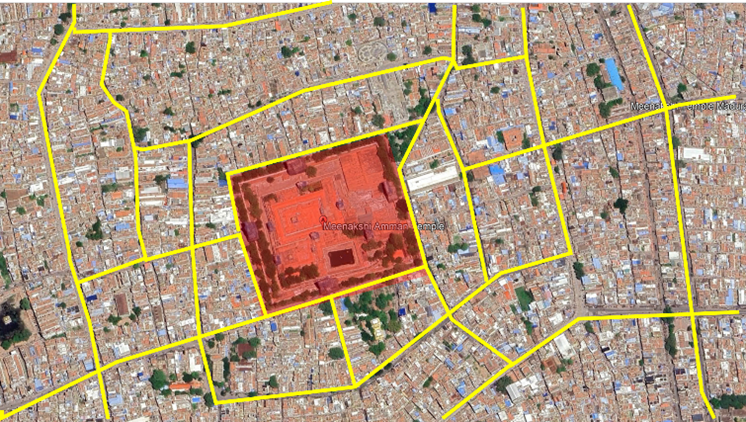

Sacred Urban Core: Temple as City Centerpiece

What sets the Meenakshi Temple apart from many other historic edifices is that it formed the geometric and functional core of Madurai itself. The city evolved in concentric rectangular streets radiating outward like the petals of a lotus — a planning idea aligned with sacred spatial order and ritual movement. This arrangement reflects the Vastu Shastra notion that the temple should be the center of both spiritual and urban life.

A city plan showing the temple at the center with patterned streets.

(Source: Google Earth Pro, https://www.istockphoto.com/)

Evolution from Pandyan beginnings → Nayak reconstruction → Modern cultural significance.

Vastu Principles: From Micro to Macro Harmony

At its core, the Meenakshi Temple embodies Vastu Shastra — a cosmic framework that shapes sacred space. The temple’s axis aligns with the east, allowing the rising sun’s first rays to illuminate the sanctums and symbolizing spiritual awakening and cosmic harmony.

Within Vastu theory, a temple is more than bricks and mortar; it is a manifestation of the Vastu Purusha Mandala, a metaphysical grid that links architecture with cardinal directions and elemental forces. As devotees move inward through successive courtyards and prakaras (enclosures), they follow a ritualized path from the external world into the spiritual center. This progression represents layered purification — both symbolic and climactic — creating a gradual transition in experience and temperature.

The sacred pond within the complex — known as the Golden Lotus Tank — is more than a ritual water body. Located strategically, it serves as a passive cooling mechanism, contributes to water conservation, and complements Eastern Vastu prescriptions for water’s placement near sacred precincts. Scholars note that such water features also function as early rainwater harvesting systems integrated within temple ecosystems.

Also Read: Matrimandir, Auroville — Architecture, Features and Importance

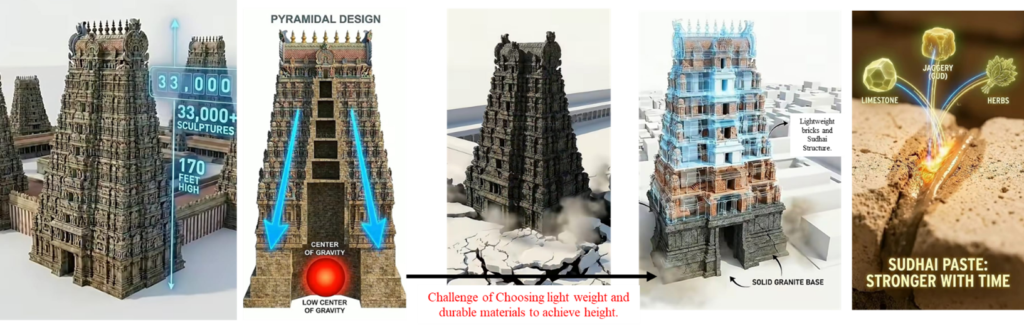

Structural Logic: Mass, Balance, and Resilience

The towering gopurams (gateway towers) of the Meenakshi Temple — some reaching nearly 170 feet — are engineering wonders. Their design follows a tapered, pyramidal form, a configuration that naturally provides structural stability and gravitational balance. The base consists of heavy granite blocks, while upper sections use lighter bricks and lime, reducing mass at higher elevations — a principle similar to modern concepts of reducing slope weight to resist overturning moments.

Ancient engineering systems are visible in the interlocking stone masonry, where precisely carved blocks fit together like three-dimensional puzzles. This system allows walls and towers to flex slightly under stress rather than crack, a principle resembling contemporary “base isolation” techniques that help structures resist seismic forces.

The foundations of the temple are also notable for alternating layers of granite, sand, and lime mortar, creating natural shock-absorbing layers that dissipate earthquake forces — a phenomenon modern engineers study as “damping systems” that reduce vibrations transmitted to the structure. Such sophisticated foundation engineering reveals an intuitive understanding of soil mechanics and earthquake resilience centuries before modern mechanics theories.

(Source: Historic Boy Mohit. (2025). Meenakshi Temple engineering reel. Instagram.)

Materials and Ancient Construction Techniques

Granite was the principal material used in the temple’s construction. Chosen for its hardness and durability, granite block sizes vary from medium slabs to massive stone units weighing several tons. These were quarried, transported, and carved with remarkable precision — befitting both structural and sculptural purposes.

The lime mortars binding these massive stones were traditionally mixed with organic additives such as jaggery and plant extracts. This combination provided flexibility and adhesion without becoming brittle over time. Studies of surviving joints indicate that these organic components also contribute to joints’ self-healing properties, a natural mechanism for long-term durability under environmental stress.

Acoustics and Sound Engineering

The temple’s Aayiram Kaal Mandapam (Hall of a Thousand Pillars) has fascinated scholars for decades. Each of its 985 intricately carved pillars was planned not only for structural support but also for sound behavior. Researchers note that the distribution of convex surface sculptures and randomly oriented pillars helped diffuse sound waves, minimizing echoes and creating an acoustically balanced environment long before modern acoustic design was understood.

Certain pillars were crafted to produce distinct musical notes when struck — a remarkable combination of stone density, geometry, and resonance frequency optimization. Modern acousticians refer to this as empirical sound engineering, where physical form and material properties together influence audible outcomes.

Some scholars also suggest that underground passages and acoustic tunnels were intentionally designed to support ceremonial sound propagation, using naturally reflective geometries akin to parabolic reflectors that focus specific frequencies — a technique reminiscent of advanced sound engineering.

(Source: Historic Boy Mohit. (2025). Meenakshi Temple engineering reel. Instagram.)

Environmental Engineering and Passive Systems

Unlike modern buildings that depend on mechanical systems, the Meenakshi Temple uses passive environmental control strategies. The thick granite walls act as thermal mass, reducing heat gain during the day and releasing it slowly at night, thus moderating interior temperatures.

High ceilings and open courtyards promote cross-ventilation, while the water tanks help cool the surrounding air through evaporation. These design strategies echo contemporary sustainable architectural principles like passive cooling, thermal stratification, and integrated water management — all embedded organically within the temple’s spatial design.

Also Read: Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School: A Desert Jewel Reimagining Architecture, Culture, and Empowerment

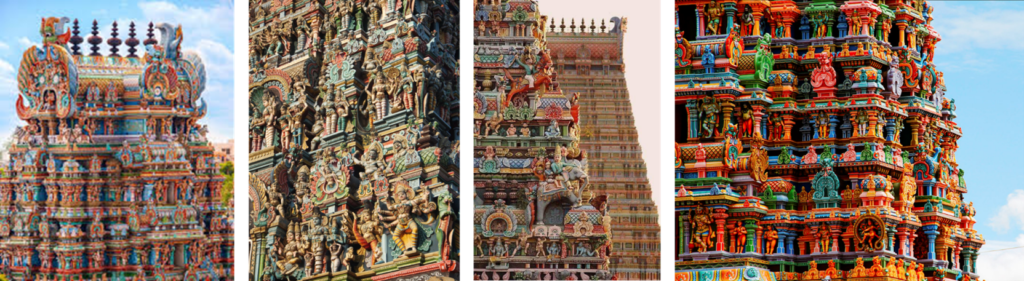

Architectural Elements, Carvings, and Use of Colour

The Meenakshi Amman Temple represents a holistic architectural language in which structure, sculpture, and colour operate as a single expressive system. Planned in the classical Dravidian tradition, the temple is organized through concentric prakarams that gradually lead devotees from the profane city into the sacred core, reinforcing a clear spatial and spiritual hierarchy. Monumental gopurams rise at cardinal points, acting as visual anchors within Madurai’s urban fabric, while expansive mandapams—most notably the Hall of Thousand Pillars—demonstrate precision in column spacing, stone craftsmanship, and structural rhythm, enabling large congregational and ceremonial use.

These architectural elements are inseparable from the temple’s sculptural richness. Nearly every surface is carved with deities, celestial beings, mythical animals, and narrative panels illustrating Shaivite and Shakta legends, particularly those associated with Goddess Meenakshi and Lord Sundareswarar. The carvings are not ornamental alone; they function as visual scriptures, communicating cosmology, ritual practices, and moral codes to devotees through form and symbolism. The figures exhibit dynamic postures, refined proportions, and intricate detailing, reflecting advanced knowledge of iconography, material behavior, and stone-working techniques.

Colour further amplifies this architectural and sculptural expression. The gopurams are covered with vividly painted stucco figures using traditional mineral pigments in blues, greens, reds, yellows, and whites. Each hue carries symbolic meaning—blue for the cosmic and divine, green for fertility and life, red for power and auspiciousness, yellow for knowledge and prosperity, and white for purity. Periodic ritual repainting during kumbhabhishekam ensures that the temple remains visually vibrant and ritually renewed, reinforcing its identity as a living monument rather than a static relic. Together, architectural form, carvings, and colour create a powerful multisensory sacred environment where art, engineering, and spirituality are seamlessly interwoven.

Why Meenakshi Temple Matters Today

The Meenakshi Amman Temple is not merely a place of worship. It is a living repository of ancient knowledge systems, where Vastu Shastra, geometry, materials science, acoustics, and structural engineering converge. Its survival through centuries — including seismic events that damaged many modern buildings — highlights the intelligence of its design and construction systems.

In an age focused on sustainability, resilience, and cultural continuity, the Meenakshi Temple remains relevant not because it is old, but because its design answers questions that modern architecture still seeks to solve.

References

- Engineers and Architects of America. (2025). Meenakshi Temple, Madurai, India: Architectural marvel of southern India.

- Hindu Vigyan. (2025). Meenakshi Temple earthquake-proof ancient seismic engineering marvel.

- Indosphere. (2025). Majestic Meenakshi Temple, Madurai: Architectural splendor and engineering.

- Tamilandvedas.com. (2017). Thousand Pillar Hall – An acoustic marvel in Meenakshi Temple.

- Massachusetts … Engineering & technology in India: Meenakshi Temple architecture (2016).

- Wikipedia. (2026). Meenakshi Temple.