ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤਸਰ, अमृतसर, امرتسر, AMRITSAR

Streets as the Soul of Amritsar

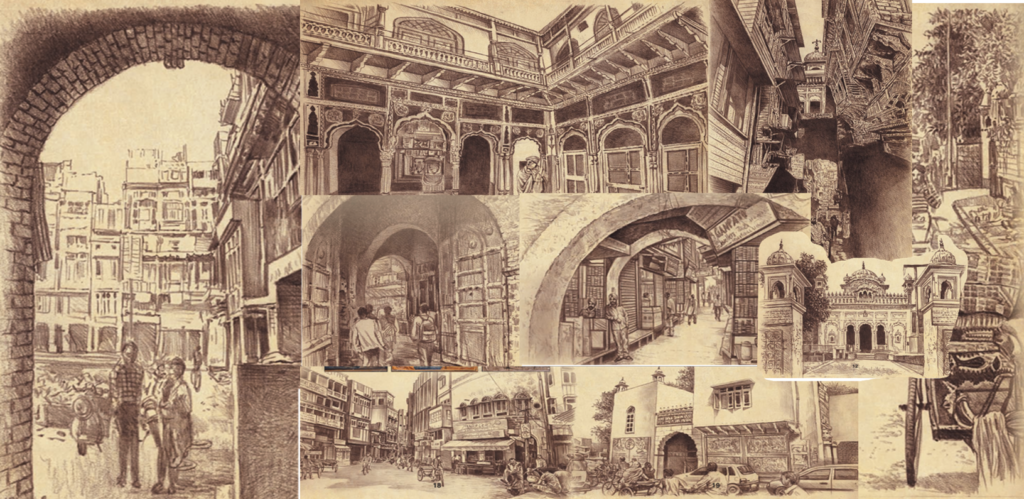

Amritsar’s identity is inseparable from its streets. More than physical corridors, they function as sacred routes, commercial lifelines, and social spaces, carrying centuries of collective memory. While the Golden Temple stands as the spiritual nucleus, it is the surrounding heritage streets of the walled city that sustain the city’s everyday urban life.

In recent years, initiatives such as the Heritage Street redevelopment have brought global attention to Amritsar’s historic core. Yet, these streets cannot be understood merely as beautified promenades; they are products of layered historical evolution, deeply rooted in Sikh philosophy, indigenous urbanism, and adaptive planning practices.

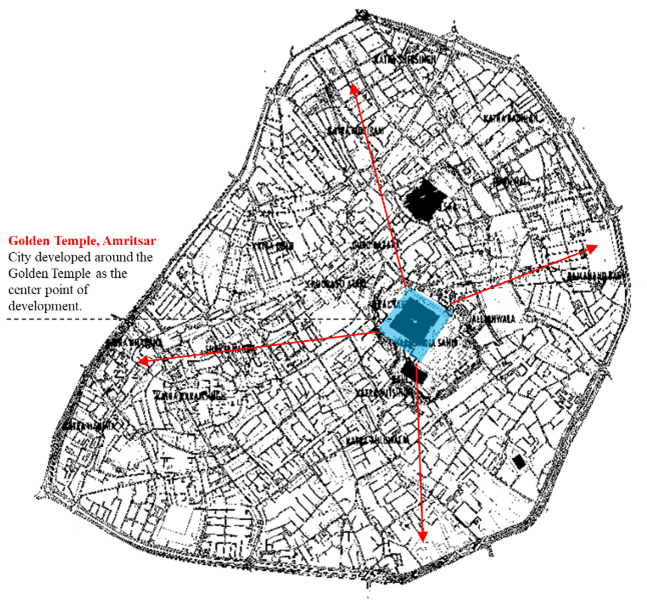

The Walled City of Amritsar: An Organic Urban Form

The historic core of Amritsar developed as a compact, pedestrian-oriented settlement, enclosed within fortified walls and accessed through twelve historic gates. Unlike imperial Mughal cities with formal axial planning, Amritsar evolved organically, guided by religious, social, and economic needs rather than royal decree.

The walled city is characterized by narrow, winding streets (galis and kuchas), Dense mixed-use development, Mohalla-based community clusters, and strong pedestrian dominance.

This morphology ensured climatic comfort, social surveillance, and vibrant street life, principles now echoed in contemporary sustainable urbanism.

Also Read: “Land Pooling or Land Losing? How Punjab’s Policy Failed Ludhiana’s Urban Vision”

Sacred Streets and Early Urban Structure (16th–18th Century)

The earliest streets of Amritsar emerged around the Sarovar of Harmandir Sahib, forming radial and concentric patterns. These streets were primarily processional routes, connecting religious institutions such as bungas, akharas, and dharamsalas. Streets were deliberately narrow to provide shade, encourage pedestrian movement, and foster community interaction. Land use along these streets was inherently mixed—residences, religious buildings, and shops coexisted—reflecting Sikh principles of collective living and equality.

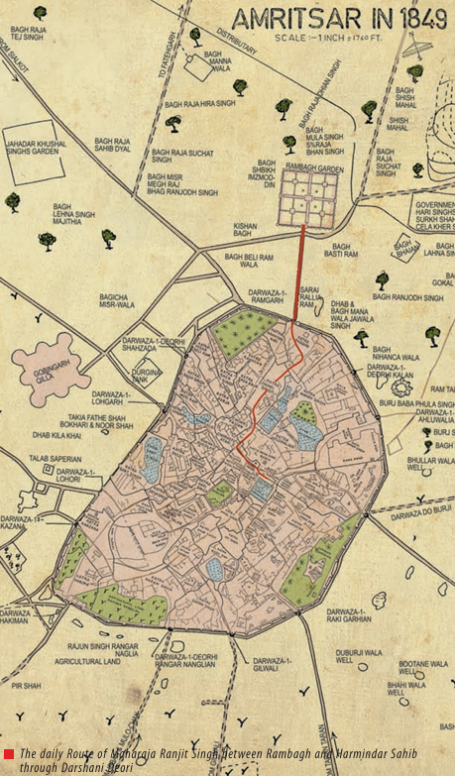

Sikh Confederacy and Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Era (18th–Early 19th Century)

With the rise of Amritsar as a political and economic center, the city acquired defensive walls and twelve gates, each acting as a key urban node. Major streets connected these gates to the central religious precinct, forming primary commercial spines.

Street hierarchy became clearly defined, with broad bazaar streets near gates, secondary lanes branching inward, and tertiary residential kuchas

This hierarchy facilitated trade, security, and neighborhood identity while maintaining walkability.

Colonial Period: Infrastructure Without Erasure (1849–1947)

During British rule, Amritsar experienced limited intervention within the walled city. While new areas like Civil Lines were planned on gridiron patterns, the historic core largely retained its structure.

Colonial interventions focused on paving and drainage of streets, street lighting, signage, and the creation of the Town Hall (1866) as a civic anchor.

The route connecting Town Hall to the Golden Temple gradually became an important ceremonial axis—later transformed into today’s Heritage Street.

Post-Independence: Congestion and Commercial Pressure (1947–2000)

Post-Partition migration intensified density within the walled city. Streets became heavily commercialized, accommodating wholesale trade, informal vending, and pilgrimage traffic.

Challenges included are encroachments, visual clutter, vehicular intrusion, and infrastructure overload. Despite these pressures, the original street geometry remained intact, demonstrating the resilience of traditional urban form.

Also Read: Sir Patrick Geddes: The Thinker Who Reimagined How Cities Grow

Heritage Street Project: Reinterpreting Historic Streets (Post-2010)

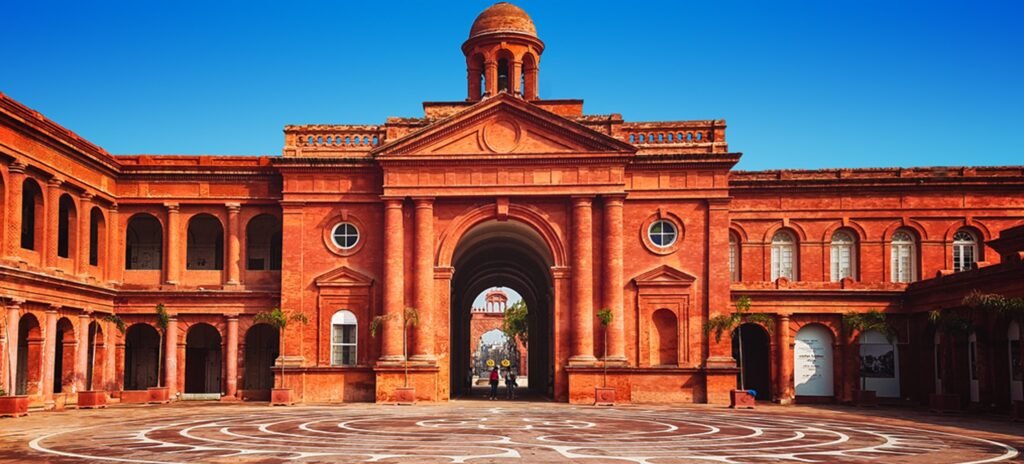

The Heritage Street redevelopment (2016) marked a paradigm shift in Amritsar’s urban planning approach. Stretching approximately 1.1 km from Town Hall to the Golden Temple, it was conceived as India’s first large-scale pedestrianized heritage corridor.

The Heritage Street redevelopment in Amritsar represents a significant shift in urban planning approach, where the street is treated not merely as a movement corridor but as a public cultural space. The project introduced complete pedestrianization, eliminating vehicular traffic to restore the traditional walkable character of the historic route and ensure a safe, uninterrupted experience for pilgrims and visitors. To maintain visual harmony and reinforce historic identity, around 170 buildings were provided with uniform heritage-style façades, drawing inspiration from local architectural elements such as arches, jharokhas, and traditional proportions. Modern infrastructure requirements were addressed sensitively through the undergrounding of utilities, removing overhead wires and reducing visual clutter that previously obscured historic views. The street was further enhanced with carefully designed street furniture, heritage lighting, and wayfinding signage, improving comfort, accessibility, and legibility without overpowering the historic setting. Together, these interventions culminate in the careful visual framing of the approach to the Golden Temple, allowing the sacred precinct to emerge gradually and ceremonially, echoing the historical experience of arrival while aligning with contemporary urban design and conservation principles.

The project sought to revive the original pedestrian and ceremonial nature of historic streets, aligning modern planning with traditional urban values.

Beyond the Main Corridor: Network of Heritage Streets

Planning documents now recognize multiple heritage streets within the walled city, including Katra Ahluwalia, Ramsar Road, Old Lakkar Mandi, and Old Tea Market Street. These streets connect historic gates, markets, gurudwaras, and residential quarters, forming a continuous cultural network.

Heritage Walks: Streets as Storytelling Devices

The Amritsar Heritage Walk uses streets as narrative tools, revealing stories of craftsmen, traders, reformers, and freedom fighters embedded in everyday spaces. It reinforces the idea that streets are intangible heritage, not just physical infrastructure.

Challenges and Planning Concerns

Despite their visual and economic success, Amritsar’s heritage streets continue to face significant urban and management challenges that threaten their long-term sustainability. The intense concentration of pilgrims and tourists, especially during festivals and peak seasons, has led to severe overcrowding, placing enormous pressure on pedestrian space, sanitation systems, and emergency access. This constant footfall accelerates wear and tear of paving materials and street infrastructure, revealing gaps in routine maintenance and drainage systems, particularly during monsoon months when waterlogging has been repeatedly reported. In addition to physical stress, the transformation of heritage streets into high-value tourist corridors has raised livelihood concerns among traditional shopkeepers and residents, many of whom fear displacement, rent escalation, or restrictions on long-established trade practices. Moreover, the growing emphasis on tourism risks turning these historic streets into commercialized spectacles, where souvenir shops and standardized retail gradually replace local crafts, everyday services, and residential uses. Such trends risk eroding the authentic social fabric that originally gave these streets their heritage value. Together, these challenges highlight the urgent need for inclusive and participatory heritage planning, where conservation efforts are balanced with infrastructure capacity, local economic needs, and the rhythms of everyday urban life, rather than focusing solely on aesthetic enhancement or tourist appeal.

Planning Lessons from Amritsar’s Heritage Streets

From an urban planning perspective, Amritsar clearly demonstrates that organic street networks are fundamental to social vitality, as their human-scale dimensions, irregular alignments, and intimate public spaces naturally encourage interaction, surveillance, and community life. The city’s historic streets also illustrate how mixed-use development embedded within heritage environments can generate strong economic resilience, allowing religious activity, commerce, housing, and informal services to coexist within walkable distances. Furthermore, the pedestrian-oriented nature of these streets—characterized by narrow widths, shaded edges, and active frontages—proves that such environments are inherently sustainable, reducing dependence on motorized transport while enhancing thermal comfort and public health. Most importantly, Amritsar underscores a crucial planning lesson: heritage conservation must prioritize continuity of use, community, and spatial logic rather than mere cosmetic beautification. When historic streets are treated as living urban systems rather than static visual artifacts, they retain relevance and authenticity. Together, these qualities demonstrate how principles of historic urbanism can meaningfully inform contemporary planning practice, particularly for dense Indian cities with active heritage cores, aligning closely with national urban design and conservation frameworks.

Streets as Living Urban Heritage

The heritage streets of Amritsar are not frozen relics; they are living, evolving urban spaces. Rooted in faith, shaped by history, and reinterpreted through planning, they embody a rare continuity between past and present.

For planners, historians, and citizens alike, Amritsar offers a compelling lesson: when streets are respected as cultural assets, cities retain their soul even as they modernize.