Abstract:

Access to education is a fundamental entitlement, yet in our country, it remains uneven -particularly in rural and semi-urban regions where infrastructural and institutional gaps persist. As cities continue to dominate the landscape of higher education, the resulting imbalance drives migration and reinforces developmental disparities. This underscores the need for decentralized models that bring education closer to underserved populations. Urban Anchor

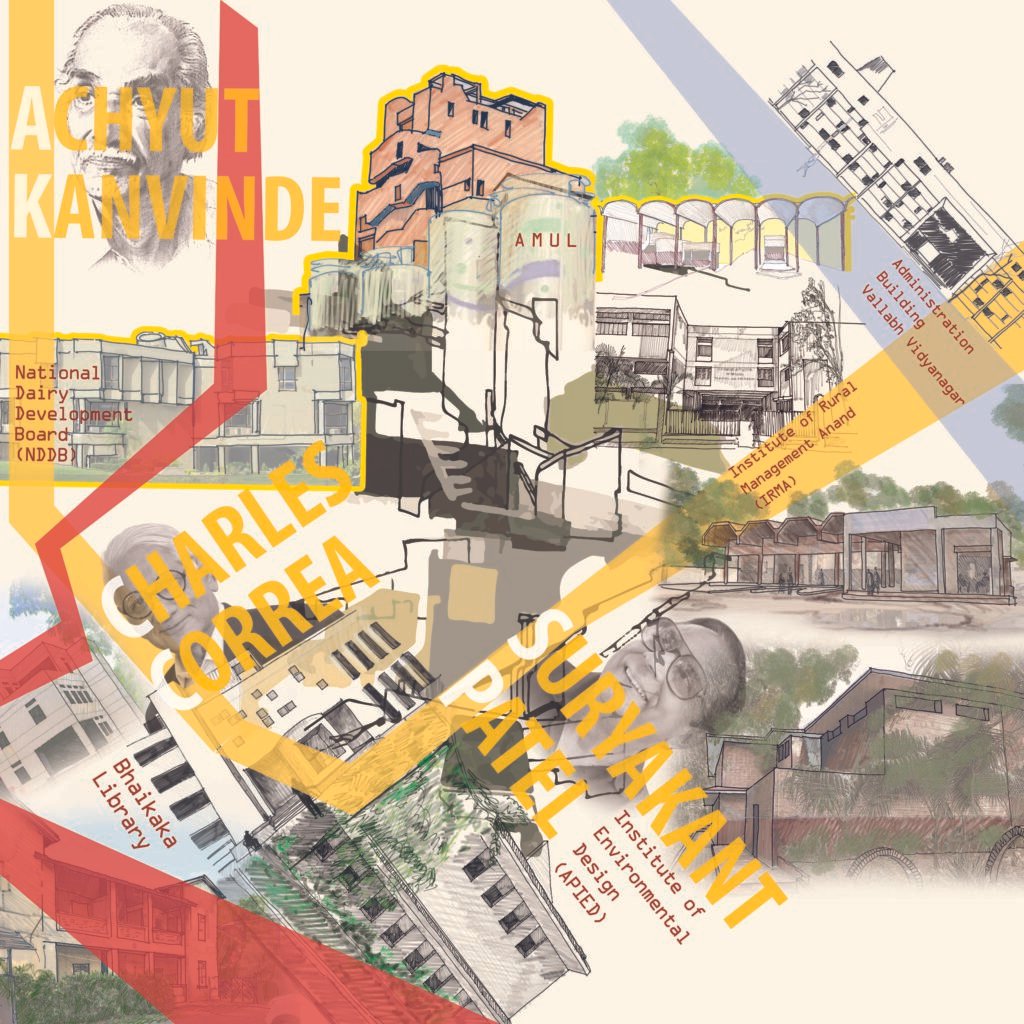

Vallabh Vidyanagar, a town in Gujarat, stands out as a rare example where education was not an afterthought, but the central idea around which the town was envisioned. This article presents Vidyanagar as a case study in how academic institutions can anchor inclusive and sustainable urban development. Located between Ahmedabad and Vadodara, major cities with rich heritage and rapid development; this town grew around institutions rather than pushing them to the periphery. With contributions from architectural stalwarts like Charles Correa, Achyut Kanvinde and Suryakant Patel, a layout rooted in walkability, greenery, and civic life, Vidyanagar exemplifies how academic institutions can anchor inclusive and sustainable urban development.

Introduction

Before independence, India’s higher education was largely concentrated in colonial urban centers like Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. This created a systemic imbalance, leaving rural regions underserved and reinforcing patterns of migration that deepened regional disparities. Gujarat mirrored this trend, where access to advanced learning was largely confined to major cities.

In 1945, Shri Bhaikaka and Shri Bhikhabhai Saheb proposed a bold alternative: to place education at the center of rural development. What if education itself could become the foundation for a new town?

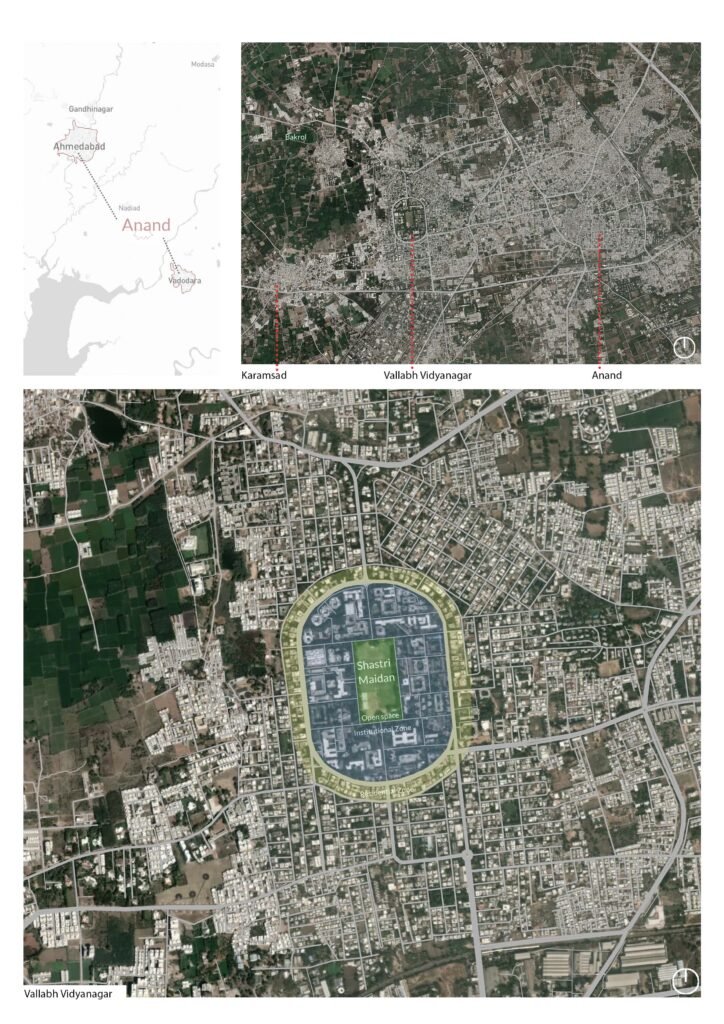

Their vision was not to append institutions to existing cities but to establish a town where education would be the organizing principle. With generous land contributions from nearby villages – Bakrol, Karamsad (birthplace of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel – a key leader in India’s independence movement), and Anand – this vision began to take physical form.

The masterplan, developed by the Ahmedabad-based firm Amin Desai, articulated a model for a “Green Town” – integrating educational, residential, and civic life through a legible and climate-responsive urban framework. The town was structured into three concentric zones: a civic core, an institutional belt, and peripheral housing. This configuration reflected a clear prioritization of public life and knowledge-based activity at the center of urban experience.

At the heart of the plan lies Shastri Maidan, a large open ground that functions as the town’s civic anchor. More than a recreational space, it has historically served as a site for collective expression – from cricket matches to political gatherings – reinforcing the town’s participatory ethos. Framed by tree-lined avenues and shaded seating, it embodies the integration of landscape and civic identity.

Vidyanagar’s street network follows a hierarchical system designed for both mobility and comfort. Roads are wide enough for vehicles yet remain scaled to the pedestrian. Continuous tree cover along most streets provides shade, mitigates heat, and fosters walkability. Buildings are generally set back, creating intermediate zones that blur the line between public and private – allowing for community interaction, passive surveillance, and spatial porosity.

What sets Vidyanagar apart is its ecological sensibility. Its layout is punctuated by pocket parks, gardens, and shaded reserves – so well-distributed that one never walks more than five minutes without encountering a restful green space. These spaces are lived-in and active, accommodating a range of users – from students to the elderly – and sustaining local biodiversity through mature native trees. The urban fabric is compact but varied, offering a coherent experience through a sequence of courtyards, shaded streets, and modest civic spaces. The design promotes a pedestrian-first culture and a built environment responsive to both climate and community. In Vallabh Vidyanagar, education was not only a programmatic need but an urban strategy.

Shaped by History

While Bhaikaka was drawing up blueprints for an education-centric town, a silent revolution was taking place nearby in Anand. In 1946, local farmers, frustrated by exploitative milk trading practices, turned to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who suggested they take control through cooperative ownership. This moment led to the birth of NDDB ( National Dairy Development Board) and Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers Union Limited, which later became AMUL; catalyzing India’s White Revolution.

Together, Vallabh Vidyanagar and Anand formed a unique ecosystem where intellectual advancement supported economic empowerment. Rather than urban sprawl or industrial exploitation, this was a model where knowledge and community ownership jointly propelled development.

Positioned between Anand’s emerging cooperative economy and the historic village of Karamsad – the birthplace of Sardar Vallabhbahi Patel – Vidyanagar was spatially and culturally rooted. Karamsad, with its tight-knit vernacular settlements and agrarian rhythm, offered a contrasting yet complementary influence. It provided a lived reference of traditional Gujarati village life, subtly informing the human-scale planning and community-oriented ethos of the new town. In post-independence India, this alignment of educational infrastructure, cooperative enterprise, and vernacular heritage presented a rural development paradigm where learning, livelihood, and legacy were intricately linked.

Architecture as Institution

As Vallabh Vidyanagar’s foundational ideas matured, they attracted some of India’s most respected architects, whose works would profoundly shape the region’s visual and functional identity. Achyut P.Kanvinde, a pioneer of Indian modernism, was commissioned to design key facilities including the Cattle Feed Plant in 1962, the NDDB campus in 1965, and the AMUL Dairy Plant in 1970. Kanvinde’s architectural language-characterized by minimalist yet monumental forms, exposed concrete, brick volumes, and deep shading devices-responded directly to Anand’s hot, arid climate, balancing utility with thoughtful expression.

The town’s close proximity to Ahmedabad, a major urban and architectural hub, facilitated the engagement of eminent architects. Among them was architect Charles Correa, a modernist visionary known for seamlessly integrating contemporary design with local tradition and climate. Invited by Bhaikaka, Correa designed several buildings on the Sardar Patel University (SPU) campus, skillfully balancing mass and void, indoor and outdoor spaces, and shade and light. His design employed courtyards, covered walkways, and low-rise structures that reflected both modern architectural thinking and a deep sensitivity to Gujarat’s context.

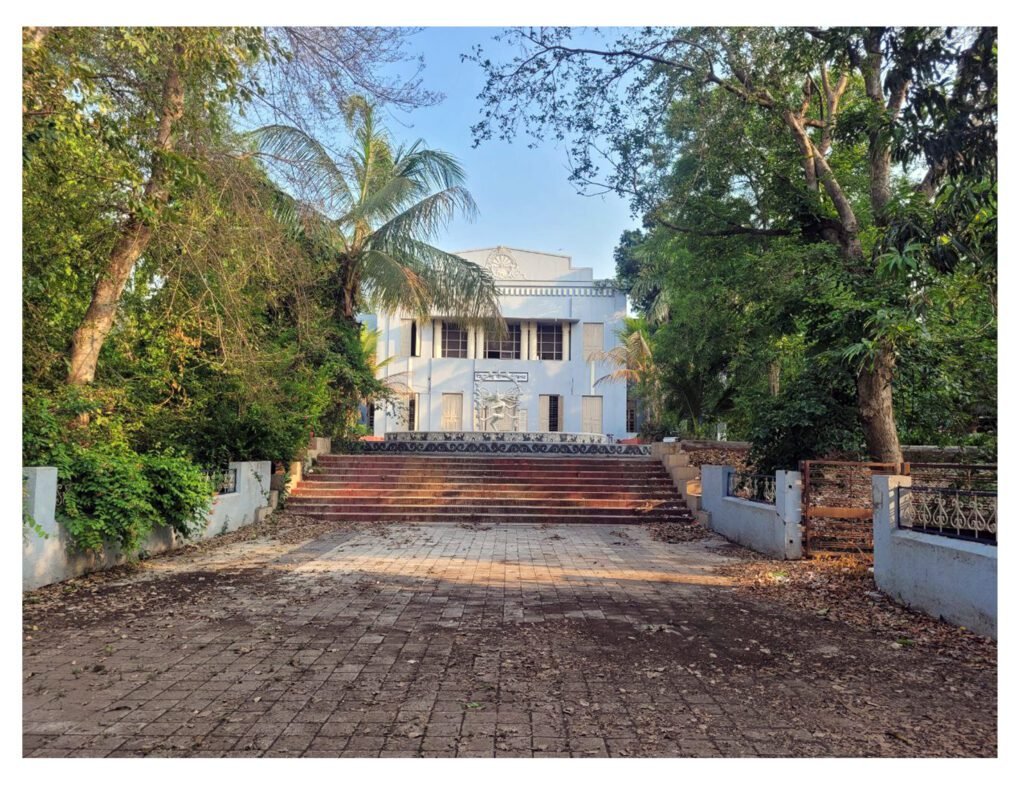

Another key contributor was Suryakant Patel, recognized for his nuanced blending of modernist principles with regional architectural heritage. In the 1980s, he designed, the Institute of Environmental Design – IED (now Arvindbhai Patel Institute of Environmental Design – APIED), the Sardar Patel Memorial, Karamsad Medical College, and many more institutional buildings. His work is marked by a careful attention to context, materiality, and climate, producing environments that are both functional and evocative. Far beyond mere responses to programmatic needs, these buildings stand as architectural statements reinforcing the region’s status as a vibrant cultural and intellectual center.

Together, these institutions – SPU (Sardar Patel University), CVM (Charotar Vidya Mandal), IED (Institute of Environmental Design), Bhaikaka Libarary, Science College, BVM (Birla Vishvakarma Mahavidyalaya) and many other institutes form a constellation of campuses linked not only by proximity but also by a shared vision. Spatially, they are unified through tree-lined avenues, shaded courtyards, and low-rise buildings with generous overhangs, creating a cohesive architectural rhythm that transcends individual authorship and reflects the collective identity of the region.

While Vallabh Vidyanagar continues to uphold the core ideals of its founding vision, it now finds itself at an inflection point – not from internal dysfunction, but from the natural evolution of its context. The town’s deliberate, education-centric model has enabled it to maintain its human-scaled identity and walkability, even as growth unfolds at its edges and the surrounding urban region expands. Unlike many cities where expansion compromises pedestrian access, Vidyanagar has retained its walkability and microclimate. However, its infrastructure – roads, public spaces, and utilities – originally designed for a smaller population, is beginning to show signs of aging. While not yet obsolete, these systems will need thoughtful upgrades to remain responsive to the steadily rising number of students, residents, and visitors.

Additionally, the growing urban footprints of Anand and Karamsad – once distinct entities – are gradually overlapping with Vidyanagar’s physical and functional boundaries. This convergence is not a conflict, but a shift in regional urban structure. It calls for renewed coordination in planning, mobility, and ecological continuity across what is becoming a more interconnected urban cluster.

The architectural and landscape heritage of the town, including buildings from the early post-independence era, needs careful stewardship. As institutions grow and adapt, the challenge is not just expansion but conservation – finding ways to integrate new functions without losing the material and spatial language that gives Vidyanagar its distinct identity.

As the physical boundaries of Anand and Karamsad begin to converge with those of Vidyanagar, the town finds itself embedded in a growing urban cluster. What were once distinct settlements are now part of a more integrated regional landscape. This shift is less about territorial overlap and more about shared futures – requiring collaborative planning, especially in mobility systems, ecological networks, and public infrastructure. The challenge now lies in maintaining Vidyanagar’s unique scale and identity while participating in this larger urban dialogue.

In this context, the role of educational townships like Vidyanagar becomes even more critical. As India grapples with overcrowded cities and underdeveloped rural areas, decentralised educational hubs offer a compelling alternative. They can anchor regional development, retain local talent, and respond directly to contextual needs – from agricultural innovation to climate adaptation. Vidyanagar’s enduring relevance lies in this integrated approach: not just as a campus town, but as a blueprint for how education, ecology, and community can shape equitable and sustainable growth.

Vallabh Vidyanagar showed what’s possible – India needs more such models to build a balanced and inclusive future.

About Authors –

Nikita Jain and Pritesh Patel are architects with a Master’s in Landscape Architecture, currently practicing and teaching in Gujarat. Their shared interests lie in the intersection of spatial design and education—exploring how institutions shape and respond to their urban contexts. Pritesh brings over 3 years of academic and professional experience, with a focus on materiality, systems, and the integration of architecture and landscape. Nikita has over 5 years of experience in landscape architecture, with a strong grounding in site development and the layering of landscape within built environments. Together, they take a context-driven, detail-oriented approach to designing meaningful spaces.

References:

- Prof. Vibha Haresh Gajjar, (2017, April), Unique land Development process of Educational town, Vallabh Vidyanagar. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 8, Issue 4

- ‘Milk, The inspiration behind a revolution’, 2025, May- URL: https://www.amuldairy.com/history.php

Also Read: Street Vendors Act 2014: Are Our Cities Really Vendor-Friendly?