“Where geometry meets spirit, and tradition walks beside modernity.”

A Space of Vision and Order

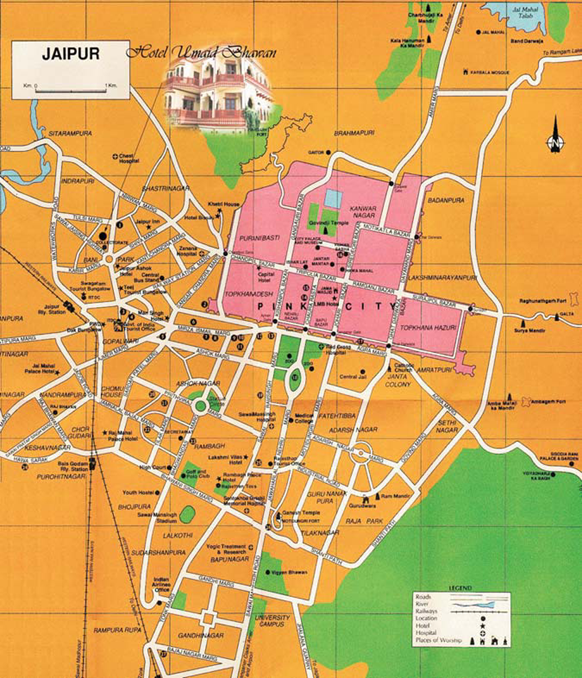

In 1727, Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II envisioned something far ahead of its time—a city designed not only for kings and warriors, but also for thinkers, traders, and travelers. His decision to shift the capital from Amber was motivated not merely by defense or space but by a deeper vision: to create a living city rooted in science, art, and harmony.

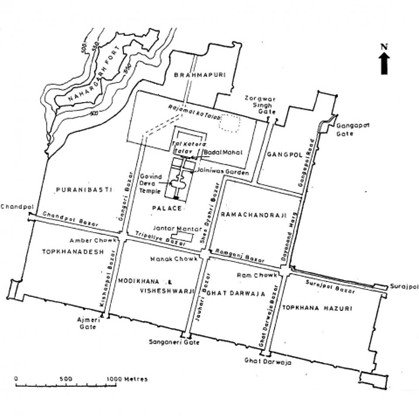

To realize this dream, he turned to Vidyadhar Bhattacharya, a Bengali architect and scholar of Vastu Shastra and Shilpa Shastra. Together, they mapped Jaipur—the famed Pink City—using a nine-grid mandala layout, aligning streets, markets, and palaces with planetary order. As the Times of India notes, “The design was heavily inspired by ancient architectural treatises that prioritized symmetry, balance, and directionality” (Times of India, 2019). Jaipur was not just a physical settlement; it was a cosmic diagram rendered in stone, lime, and sandstone.

Also Read: Street Vendors Act 2014: Are Our Cities Really Vendor-Friendly?

The Urban Geometry: Sector-Based Grid Layout and Symbolism

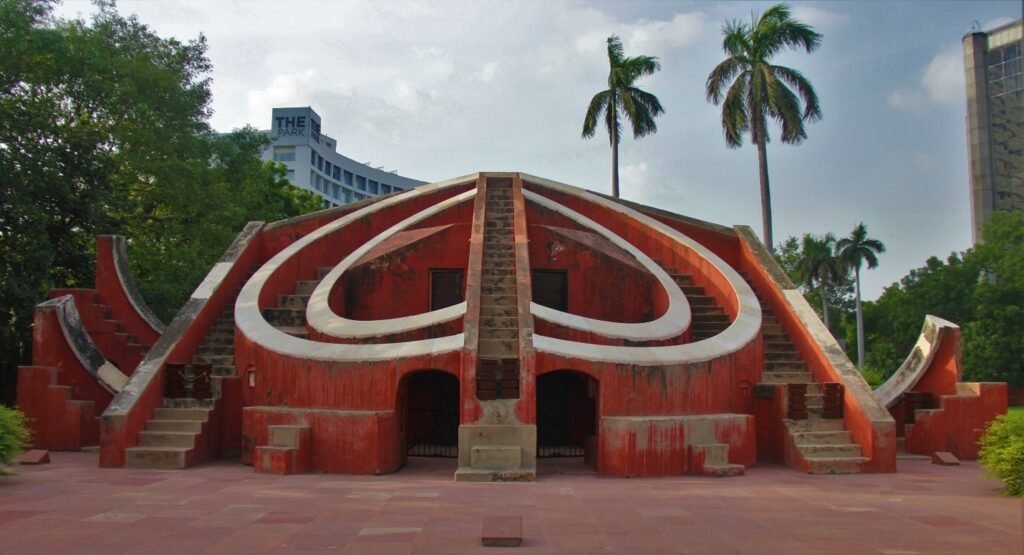

Unlike many Indian cities that evolved organically, Jaipur was conceived with intention. It was laid out in nine rectangular chowkris (sectors), each with a defined purpose—some for royalty, others for craftsmen, traders, and residents. At the center stood the City Palace and Jantar Mantar, monumental spaces with both civic and spiritual significance. “The city plan represents a rare synthesis of Indian religious ideals and pragmatic urbanism” (IndiaTV News, 2019).

This careful balance of sacred geometry and everyday functionality made Jaipur a truly exceptional urban form—protective yet open, practical yet symbolic.

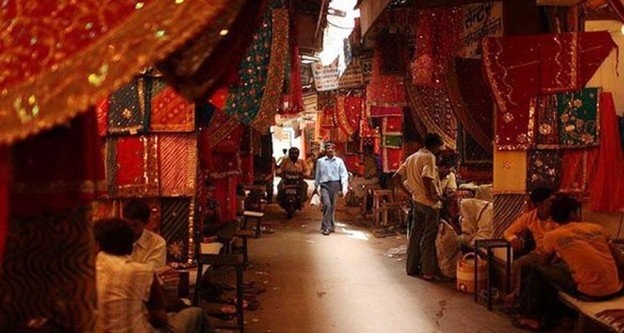

Balancing Commerce and Livelihood

Jaipur’s design was as much about economics as it was about cosmology. Roads were unusually wide—up to 111 feet—to accommodate camel carts, merchants, and pedestrians. Bazaars like Johri Bazaar and Tripolia Bazaar integrated colonnaded shops, ensuring commerce thrived in shaded, pedestrian-friendly spaces. According to the Jaipur World Heritage Committee, “Trade was seamlessly integrated into the street fabric, with markets functioning not just as commercial but as social spaces” (Ministry of Culture, GoI, 2019).

This inclusive model of urban commerce stands in stark contrast to modern malls and closed-off retail spaces.

Architectural Dialogue: Form, Function, and Identity

The city’s architecture reflects harmony and restraint. Uniform pink facades, jharokhas, chhatris, and intricately carved stone screens create a visual identity that is both welcoming and distinctive. The pink color—now iconic—was introduced in 1876 by Maharaja Ram Singh to welcome the Prince of Wales, a diplomatic gesture that became the city’s enduring identity (Times of India, 2019).

Structures such as the City Palace and Jantar Mantar (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) demonstrate how Jaipur’s architecture embodies not just beauty but also science, belief, and royal grandeur. As UNESCO noted at its World Heritage designation in 2019, “The city represents an exceptional example of a late medieval trade town in South Asia, planned to align civic life with celestial rhythms” (UNESCO, 2019).

Also Read: Dharavi Redevelopment Project: Balancing Dreams and Realities

Heritage and Hybrid Identity

In the late 19th century, under British influence, architect Samuel Swinton Jacob introduced the Indo-Saracenic style, adding colonial flourishes to Jaipur’s skyline. His work—including the Albert Hall Museum—layered new identities without erasing the old (Architectural Digest India, 2018). Jaipur thus evolved not as a frozen heritage city, but as a living continuum, adapting while preserving its essence.

Culture, Celebration, and Public Space

Jaipur’s planning comes alive in its chowpars and open squares, which transform into vibrant cultural stages during festivals like Gangaur and Teej. Streets become processional routes, alive with color, music, and dance, reaffirming the city’s deep bond between space and society.

Retrofitting the Past into the Future

Modern Jaipur demonstrates how heritage and innovation can coexist. Initiatives such as heritage walkways, pedestrian-friendly bazaars, and adaptive reuse of old havelis into cafés or museums reflect thoughtful planning. The UNESCO recognition in 2019 amplified these efforts, encouraging conservation with innovation.

Yet, challenges remain. Increased traffic, unregulated construction, and the pressures of mass tourism continue to threaten Jaipur’s balance (Hindustan Times, 2020). The city’s cautious approach—embracing smart mobility, heritage tourism, and careful renewal—offers lessons for rapidly growing Indian cities.

Conclusion

Jaipur is not only India’s first planned city; it is also one of its most felt cities—crafted by cosmology, culture, and community. Its streets are not just roads; they are threads connecting commerce, faith, and daily life.

The city reminds us that good planning is not about control but about care—about embedding joy, tradition, and belonging into urban spaces. Jaipur demonstrates that cities do not have to choose between memory and progress, beauty and functionality. If planned with vision and sensitivity, they can embody both.

Jaipur, then, is not merely a place. It is a philosophy—of harmony between people, place, and purpose.

Also Read: Chennai’s Cool Roofs: A Simple Solution to a Scorching Crisis

References

- Times of India. (2019). A Maharaja, A Bengali Architect Were Behind India’s First Planned City. Retrieved from: Link

- UNESCO. (2019). Jaipur: The Pink City inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Retrieved from: Link

- India TV News. (2019). Planning Jaipur: Cosmic Alignment in Urban Form.

- Architectural Digest India. (2018). Indo-Saracenic Legacy of Samuel Swinton Jacob.

- Ministry of Culture, Government of India. (2019). Jaipur World Heritage Nomination Dossier.

- Hindustan Times. (2020). Challenges of Urban Growth in Jaipur.