“From streets to stalls—redefining how our cities value the hands that feed us.”

Introduction

Strolling down any Indian street, the vibrant and aromatic hum of street life greets you—the sizzling of pakoras, the rhythmic chopping at a vegetable stall, and the friendly handover of tea in a small glass tumbler. Street vendors are the living, breathing arteries of our cities—fueling every child’s craving and every office worker’s break time. Street Vendors Act 2014

But beneath this warmth lies a tension: can the cities we build truly accommodate these informal lifelines?

Table of Contents

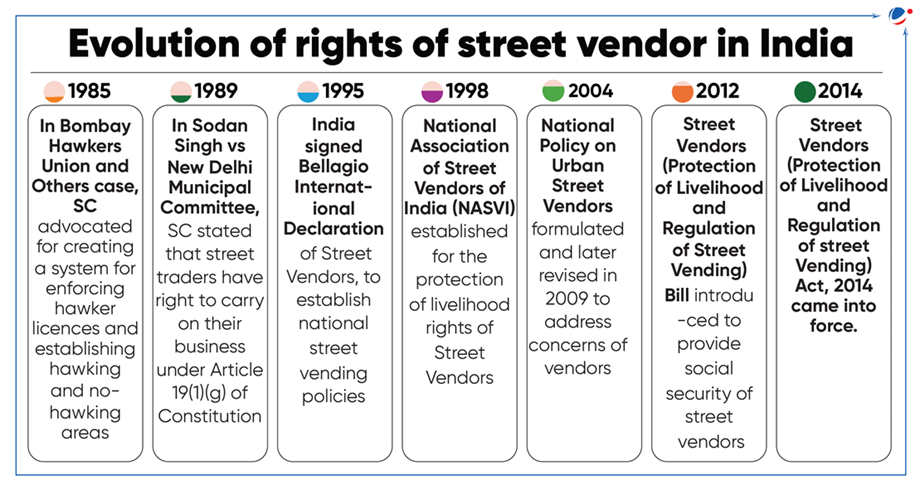

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014, promised a more inclusive urban future—securing rights for millions who feed, clothe, and serve us daily. Nearly a decade later, are our cities truly welcoming street vendors as equal urban citizens? Or are they still being pushed to the margins—legal in theory, invisible in practice?

As the Press Information Bureau once stated: “Street vendors constitute an integral part of our urban economy… It is vital that these vendors are enabled to pursue their livelihoods in a congenial and harassment-free atmosphere.” Yet, on the ground, even after the Act came into force in May 2014, vendors often remain on the fringes—trapped between policy and practice.

Reference-css.in

The Act’s Promises

The 2014 Act was more than legislation—it was a turning point in how cities viewed their pavements. For decades, street vendors were treated as intrusions, their presence tolerated but never protected. This Act flipped the script: it recognized street vending as a lawful livelihood, and street vendors as rightful urban citizens, not just “encroachers.”

The law offered significant safeguards:

- Vendors could not be evicted during peak vending hours (7–10 a.m. and 5–8 p.m.), on public holidays, or in the run-up to elections.

- It guaranteed identity cards, access to vending zones, and licenses that legitimized their work.

- It mandated Town Vending Committees (TVCs)—local bodies with 40% vendor representation—to prepare vending plans for each city.

These weren’t just bureaucratic changes; they symbolized a shift from removal to recognition, from “hawker nuisance” to “livelihood dignity.”

When I first read about this Act, I felt hopeful. It wasn’t just a policy—it was a statement that Indian cities could finally be for everyone. It acknowledged the people who wake at dawn to serve tea, sell vegetables, and mend shoes—those whose work is woven into our daily lives. The Act was the city’s way of saying: You matter too.

Reference-nasvinet.org

Implementation Hurdles: Between Paper Rules and Pavement Realities

Despite its progressive intent, real-world adoption has been slow. Reports note challenges ranging from bureaucratic delays to climate stress and unchecked evictions. In Ahmedabad, vendors legally protected from removal were still forced off the streets during infrastructure expansions.

In Chennai, newly mapped vending zones were ignored. More than 700 hawkers occupied restricted pavements near bus stops, forcing pedestrians onto dangerous roads. The Act’s intended balance between vendor rights and pedestrian safety seemed lost.

In Nagpur, despite registering over 3,000 hawkers and approving 43 vending zones, fewer than 1,300 vendors received licenses. Footpaths remained blocked, creating traffic congestion and public frustration.

The problem isn’t the law’s intent—it’s institutional inertia. When committees exist only on paper and enforcement is inconsistent, vendors pay the price.

Governance Gaps: Will TVCs Make a Difference?

Town Vending Committees were designed to bring vendors into local decision-making. However, only one-third of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) have formed TVCs, and 42% of these lack vendor representation entirely. Spaces meant for dialogue remain empty.

In Kolkata, the Hawker Sangram Committee worked with local authorities to reclaim 80% of missing pavements—showing the potential of TVCs when they function properly. True inclusion means walking into a TVC meeting and seeing vendors—not just officials—holding space.

Evictions, Harassment, and the Promise of Protection

The Act prohibits evictions without proper procedures—yet reports continue of vendors being displaced despite holding valid certificates. In Delhi, NASVI alleges recent evictions in violation of the law. In Chandigarh, the High Court had to reaffirm that street vendors are not criminals, penalizing petitioners who labeled them as such.

These incidents show that legal recognition is meaningless without enforcement.

Reference-Hindustan times

City Case Studies

Nagpur: 43 hawking zones approved, but only 1,225 licenses issued. Thousands remain unprotected.

Chennai: Over 700 vendors occupy restricted sidewalks between Aminjikarai and Koyambedu, creating safety issues for pedestrians.

Kochi: The corporation distributed 56 licensed kiosks and created vending zones for 2,351 vendors—becoming Kerala’s first ULB to implement an approved vending bylaw.

Bhubaneswar: Built permanent kiosks for 329 vendors.

Pune & Kolhapur: Issued 5,000 vending cards, strengthening vendor representation.

Infrastructure & Services

The Act includes provisions for hygiene, shade, toilets, social security, and access to credit. Yet many cities lack even basic amenities for vendors. In Mumbai, over 250,000 vendors operate without adequate sanitation, water, or storage facilities.

Reference-Times Of India

Some initiatives are promising. Under PM SVANidhi, Mysore Municipal Corporation hosted a “Loan Mela,” offering working capital and promoting digital payments. But such success stories remain the exception.

Balancing Rights: Pedestrians and Vendors

The Act aims to harmonize vendor livelihoods with pedestrian safety. Yet conflicts persist when footpaths become overcrowded. The goal should be coexistence, not exclusion—clear rules, shared spaces, and mutual respect are essential.

Lessons & Reforms

To create truly vendor-friendly cities:

- Enforce certification and surveys—no paperwork, no eviction.

- Expand and empower TVCs—ensure vendor voices hold influence.

- Invest in infrastructure—sanitation, shade, waste bins, water, and digital access.

- Educate officials and citizens—shift public perception through awareness.

- Balance space—develop protocols that respect both movement and livelihood.

Also Read: URBAN SPRAWL IN INDIA: A Threat to Sustainable Development

Conclusion

The Street Vendors Act was a beacon of hope, recognizing vendors as citizens and contributors to the urban economy. But rights without implementation are empty promises.

If we want inclusive cities, we need enforcement, infrastructure, and empathy. The soul of a city is not in spotless pavements but in the shared meals, trust, and daily interactions that street life offers. That is when our cities truly come alive—as shared homes for all.

References

- Press Information Bureau – Street Vendors Bill features theprayasindia.com+1timesofindia.indiatimes.com+1timesofindia.indiatimes.com+3pib.gov.in+3ijfmr.com+3dcmsme.gov.in+2en.wikipedia.org+2wiego.org+2

- Wikipedia – Street Vendors Act details

- IMPRI report – Decade of the Act challenges impriindia.com

- Insights IAS – Ahmedabad example impriindia.com+4insightsonindia.com+4drishtiias.com+4

- Times of India – Chennai hawkers stretch timesofindia.indiatimes.com+4en.wikipedia.org+4timesofindia.indiatimes.com+4

- Times of India – Nagpur licensing failure timesofindia.indiatimes.com+3repository.nls.ac.in+3timesofindia.indiatimes.com+3

- WIEGO – TVC participatory model wiego.org+1pib.gov.in+1

- AP News – G20 evictions in Delhi insightsonindia.com+5apnews.com+5timesofindia.indiatimes.com+5

- Times of India – Delhi evictions 2025

- Times of India – Chandigarh HC vendor ruling impriindia.com+3ccs.in+3insightsonindia.com+3

- Wikipedia – SVANidhi & Mysore en.wikipedia.org+1en.wikipedia.org+1