Cities are not just collections of buildings and streets—they are living environments shaped by how people perceive, navigate, and emotionally connect with them. Few urban thinkers have captured this relationship as profoundly as Kevin Andrew Lynch (1918–1984), the American urban planner and educator whose groundbreaking work continues to influence urban design worldwide, including in India (MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, n.d.).

Table of Contents

The Vision of Kevin Lynch

Lynch, a long-time professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is best known for his 1960 book The Image of the City (Lynch, 1960). Through studies in Boston, Jersey City, and Los Angeles, he explored how people form mental maps of their surroundings and how the physical form of cities shapes these maps.

He coined the term “legibility” to describe the ease with which a city’s layout can be understood and remembered. For Lynch, a legible city is not just easier to navigate—it fosters identity, belonging, and comfort (Southworth, 2014).

Notable Works

Kevin Lynch’s career produced a number of influential books and research projects that remain touchstones in urban design and planning:

- The Image of the City (1960) – His most celebrated work, introducing the concepts of city legibility and the five elements—paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks—that define how people understand cities.

- Site Planning (1962, with Gary Hack in later editions) – A foundational guide for planners and architects, offering systematic approaches to circulation, land use, environmental considerations, and landscape integration.

- What Time Is This Place? (1972) – An exploration of how cities relate to the perception of time, balancing historical continuity with change.

- Managing the Sense of a Region (1976) – A study of regional identity, combining natural landscapes, cultural heritage, and infrastructure in design thinking.

- Good City Form (1981) – A synthesis of his lifetime’s research, introducing performance measures such as vitality, sense, fit, access, and control to evaluate urban quality.

The Five Elements of a City’s Image

Lynch (1960) identified five core components that give a city its form in our minds:

- Paths – Routes of movement such as streets, walkways, and transit lines.

- Example: Delhi’s Kartavya Path and Mumbai’s Marine Drive are instantly recognizable paths that define the city experience.

- Insight: In India, paths often double as social spaces—markets, parades, and festivals transform them into vibrant cultural corridors (NIUA, 2021).

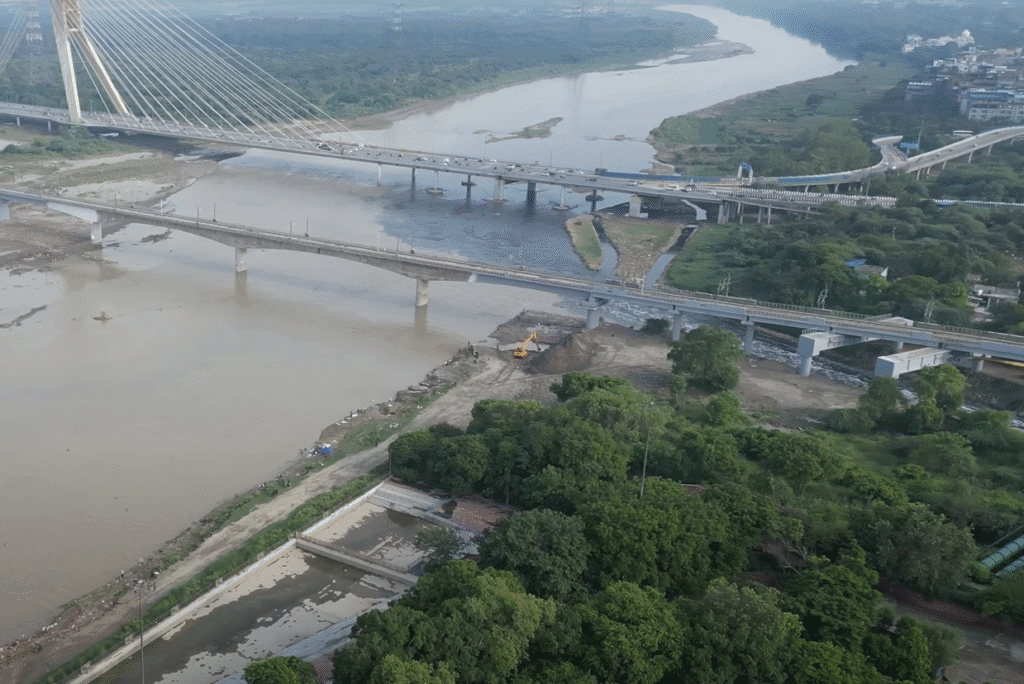

- Edges – Boundaries between areas, such as rivers, walls, or major roads.

- Example: The Yamuna River in Delhi is both a geographic divider and an underutilized public asset.

- Insight: Projects like Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Riverfront show how well-designed edges can reconnect cities with their natural landscapes (National Institute of Urban Affairs, 2021).

- Districts – Large areas with a distinct character.

- Example: Kolkata’s College Street, famous for its bookstores and coffee houses, is a unique cultural district.

- Insight: Indian districts are often defined as much by sound, smell, and atmosphere as by architecture—renewal must protect these sensory identities (Mehrotra, 2001).

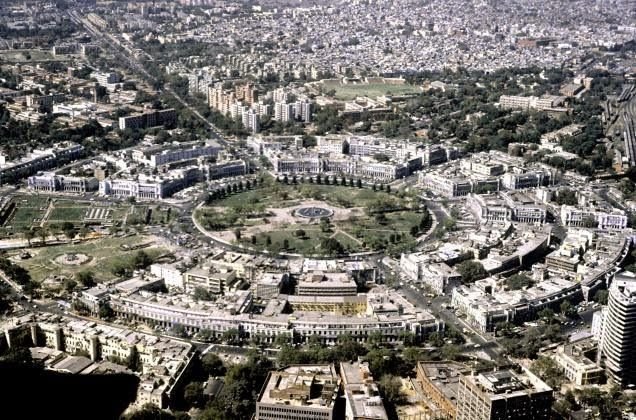

- Nodes – Strategic points for decision-making or gathering, such as intersections and plazas.

- Example: Connaught Place in Delhi functions as a commercial hub, transit interchange, and social meeting point all in one.

- Insight: In Indian cities, successful nodes are multi-functional; designing them only as traffic junctions is a lost opportunity (Banerjee & Southworth, 1990).

- Landmarks – Distinct features used for orientation, like monuments or iconic buildings.

- Example: The Gateway of India in Mumbai serves as both a tourist attraction and a navigational reference.

- Insight: The most enduring landmarks in India are culturally rooted rather than merely tall or flashy (Mehrotra, 2001).

Relevance in Today’s Indian Context

Rapid urbanization, digital navigation, and climate challenges are reshaping Indian cities, but Lynch’s framework remains strikingly relevant:

- Wayfinding in chaotic cityscapes still relies on physical cues, not just GPS (Southworth, 2014).

- District character must be preserved amidst the pressures of uniform real estate development.

- Edges can be reimagined as public spaces instead of neglected margins (NIUA, 2021).

- Nodes can strengthen resilience during crises by serving as community gathering points.

- Landmarks rooted in culture can reinforce local identity in an era of global sameness.

A Personal Take

Indian cities are often described as chaotic, but within that complexity lies a deep, intuitive order. Lynch’s theory offers a way to reveal that order—making cities more navigable without erasing their energy and diversity. The goal is not to impose rigid grids but to make our layered, sensory-rich urban environments legible and memorable.

Whether it’s the narrow ghats of Varanasi, the bustling lanes of Chandni Chowk, or the tech corridors of Bengaluru, a city should tell its story clearly, proudly, and in a way that invites people to be part of it.

Also Read: Jane Jacobs: The Heartbeat of Urban Spaces