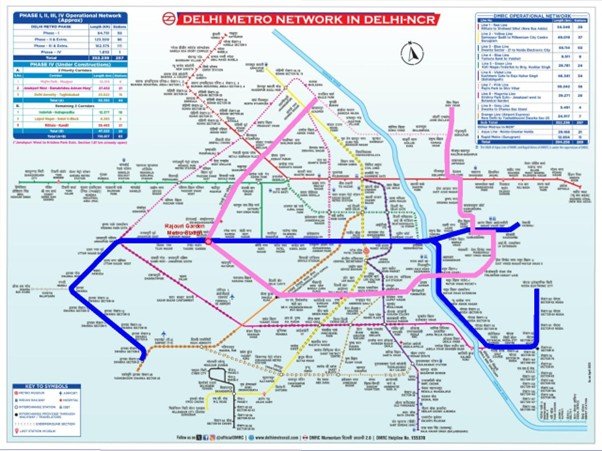

As urban India continues to expand, public transport systems like the Delhi Metro have become lifelines for millions.Rajouri Garden However, with increasing ridership comes increasing pressure on infrastructure—especially at interchange stations. A growing concern among daily commuters is the pedestrian congestion at these crucial nodes. One such example is the Rajouri Garden interchange station, where the Blue Line intersects with the Pink Line, serving as a vital connector between West Delhi, North-West, and South-East Delhi to West to east.

The Pink Line, in particular, links major commercial and transit hubs such as Lajpat Nagar, Sarojini Nagar, South Extension, Azadpur Mandi, and Sarai Kale Khan Railway Station. With five major interchange stations on this route, Rajouri Garden stands out due to the intensity of foot traffic during peak hours.

Despite the availability of facilities like escalators and travellators, commuters experience significant delays and discomfort. The walking distance between platforms can take up to 10–15 minutes, creating bottlenecks. Travellators, intended to ease movement, often become sources of frustration—especially when some commuters choose to stand still, obstructing those trying to move quickly. This results in a ripple effect of slow movement, compounded by overcrowded walkways and poor ventilation—especially during Delhi’s harsh summers.

Such conditions beg an important question: Were these interchanges designed with future user demand in mind? And if so, why do pedestrian conflicts persist so intensely?

In high-density urban environments, time is of the essence. The inability to walk freely and quickly through interchanges adds to commuter stress and delays. More critically, the lack of crowd management systems and inadequate spatial planning pose serious risks in case of emergencies or mishaps.

This case study of Rajouri Garden reveals a broader issue in metro interchange design: the need to plan for pedestrian comfort, movement efficiency, and safety—not just connectivity. A pedestrian-friendly design should consider wider corridors, better segregation of walking and standing lanes on travellators, dynamic crowd flow systems, and effective ventilation strategies.

As urban planners and architects, we must shift the conversation from capacity to experience. It’s not just about how many people a station can hold, but how comfortably and safely they can move through it. The Rajouri Garden interchange—and others like it—highlight the urgent need for a redesign strategy that prioritizes people over infrastructure alone.

Stay tuned with TheAPN with more updates