STUDENTS CONTRIBUTION: Chetan | Avinash Yadav

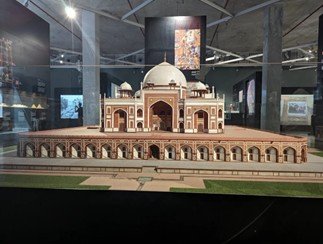

In the heart of Delhi stands a masterpiece of Indo-Persian architecture — Humayun’s Tomb, the first grand experiment of Mughal funerary architecture in India and the forerunner to the Taj Mahal. Commissioned by Haji Begum in 1565 AD and designed by Persian architect Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, this 16th-century marvel was not merely a memorial to Emperor Humayun but a statement of imperial vision, spiritual symbolism, and cultural synthesis.

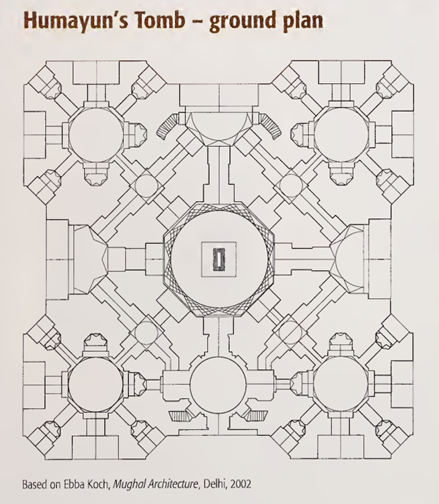

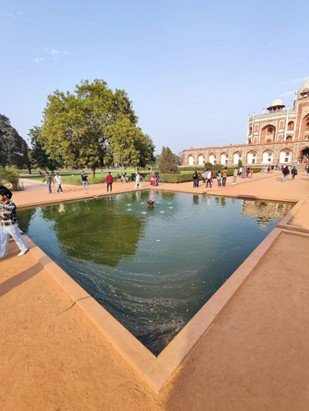

This monumental tomb introduced the Timurid concept of the charbagh (four-part garden) to India — a sacred layout echoing the Quranic vision of paradise. Flowing water channels and symmetrical gardens converge at the elevated tomb platform, placing the emperor metaphorically at the center of a cosmic order. As the Archaeological Survey of India (2002) notes, the garden “was divided into four parts by wide causeways and further subdivided into 36 squares with pathways and water channels” (p. 54–55).

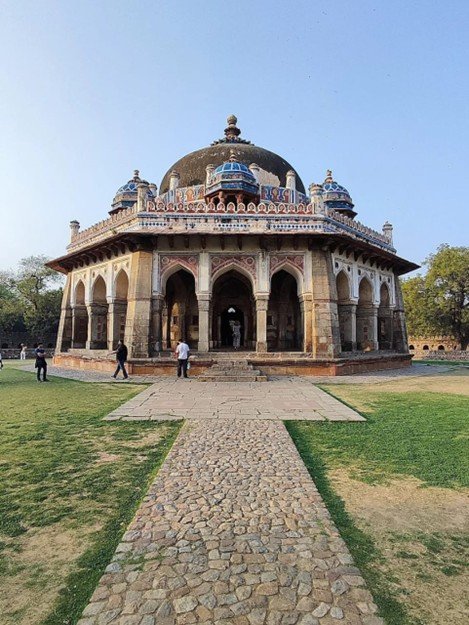

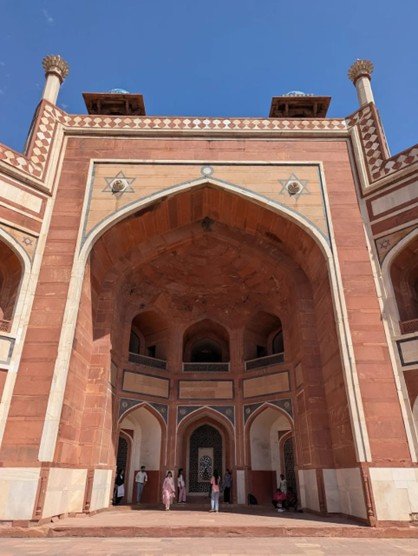

Architecturally, the tomb is an outstanding blend of Persian formal planning and Indian material ingenuity. Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, steeped in the traditions of Herat and Samarkand, introduced key Timurid features such as the double dome, iwan-style arched facades, and radial octagonal symmetry. These were reimagined in the Indian context using red sandstone from Tantpur and Makrana marble, materials that later became hallmarks of Mughal architecture (ASI, pp. 33–34).

The structure’s central chamber, octagonal in plan, is flanked by multiple subsidiary tombs, making it not just a royal grave but a dynastic mausoleum with over 150 burials. Haji Begum, Dara Shikoh, and several later emperors including Farrukhsiyar and Alamgir II lie here — a testament to its importance as a Mughal necropolis (ASI, pp. 34–35).

Decorative elements like jaalis (stone lattice screens) and chhatris (domed pavilions) reflect the synthesis of Persian and Indian design vocabularies. Jaalis, cut from single slabs, filtered sunlight into sacred patterns, while Rajput-origin chhatris added both structural relief and symbolic presence atop the monument (ASI, p. 34).

Despite centuries of neglect, the monument’s spirit was revived during a landmark restoration between 2007–2013, led by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. This conservation effort reinstated the original water channels, revived ancient wells, and trained over 150 local artisans in heritage techniques — all in alignment with UNESCO’s preservation guidelines (AKTC Report, 2020; UNESCO World Heritage Centre).

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993 under cultural criteria (ii) and (iv), Humayun’s Tomb set the architectural precedent for the Taj Mahal and Akbar’s Tomb. More than an emperor’s resting place, it remains a living monument that continues to inspire architects, historians, and citizens alike.

“The garden-tomb form, first established at Humayun’s Tomb, became the prototype for later Mughal royal tombs… combining landscape with monument.” — UNESCO World Heritage Centre

Also Read: Designing for Childhood: A Visit to National Bal Bhavan

References:

- Archaeological Survey of India. (2002). World Heritage Series: Humayun’s Tomb and Adjacent Monuments.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/232

- Aga Khan Trust for Culture. (2020). Conservation Project Report on Humayun’s Tomb.