STUDENTS CONTRIBUTION: Irshad Alam

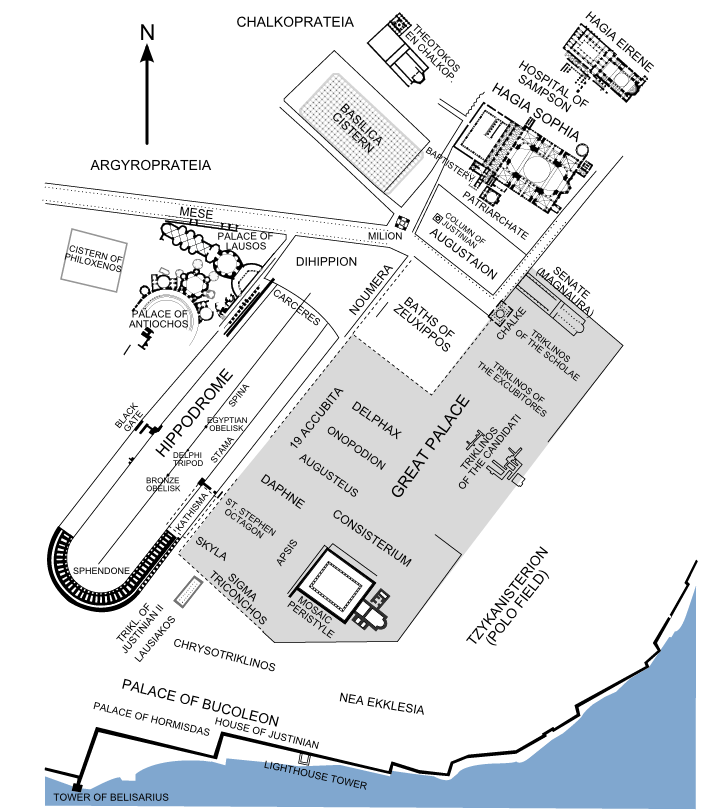

Standing at the crossroads of continents and civilizations, the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque in Istanbul is more than a monument — it is a living chronicle of 1,500 years of religious, political, and architectural evolution. Originally built as a Christian cathedral in 537 CE under Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, it was transformed into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, and later declared a museum in 1934. In 2020, it was reconverted into a mosque, reawakening its spiritual role while preserving its global cultural identity.

Image Reference– WIKIMEDIA

Table of Contents

A Legacy of Spiritual and Structural Grandeur

Commissioned during the Byzantine Empire, Hagia Sophia was envisioned as a symbol of divine wisdom and imperial might. Justinian’s architects, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, introduced groundbreaking engineering — particularly the use of pendentives — to support a vast dome 31 meters in diameter and soaring 55.6 meters above the ground. With 40 windows at its base, the dome appears to float, flooding the interior with light and spiritual resonance. This innovation influenced ecclesiastical and mosque architecture for centuries, from Renaissance cathedrals to Ottoman imperial mosques.Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque

Constructed with bricks, marble from across the empire, and gilded mosaics, Hagia Sophia was not just a church but a cosmic space, evoking heavenly perfection. Upon its completion, Justinian reportedly proclaimed, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee!”

Ottoman Transformation and Islamic Integration

Following the Ottoman conquest, Sultan Mehmed II converted the cathedral into an imperial mosque. This marked a pivotal shift, not only in the building’s function but also in its identity. Islamic architectural elements were introduced with great care, ensuring harmony with the existing Byzantine fabric. A mihrab was installed in the former apse, slightly off-center to align with Mecca, while a finely carved white marble minbar was added for sermons.

Minarets were constructed around the building’s corners — the earliest under Mehmed II and the most refined by the renowned architect Mimar Sinan during the reign of Sultan Selim II. Today, four minarets define its skyline, merging Ottoman verticality with Byzantine mass.

Perhaps the most distinctive Islamic additions are the enormous calligraphic roundels, designed in the 19th century under Sultan Abdulmecid. Suspended high on the piers of the central dome, these roundels bear the names of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, the four Rightly Guided Caliphs, and the Prophet’s grandsons Hasan and Husayn — asserting Islamic identity while coexisting with Christian mosaics beneath.

Also Read: Humayun’s Tomb: The First Great Mughal Garden Mausoleum

Christian Art Preserved Amid Change

While Hagia Sophia became a mosque, many Christian features were respectfully preserved or plastered rather than destroyed. Byzantine mosaics — such as the Virgin Mary with Child, Christ Pantocrator, and the famed Deësis — continue to adorn its upper galleries, reflecting the artistic and theological depths of early Christianity. These mosaics, made from gold, glass, and stone tesserae, glow under natural light, symbolizing divine presence.

UNESCO Recognition and Modern Controversy

In 1985, Hagia Sophia was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, acknowledged for its “outstanding universal value.” As part of the “Historic Areas of Istanbul,” it is studied worldwide across disciplines — architecture, theology, art history, and interfaith studies.

In 2020, Turkey’s top administrative court ruled that Hagia Sophia’s status as a museum violated its historical foundation deed, originally designated by Sultan Mehmed II as a mosque. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ordered its reconversion, and the Presidency of Religious Affairs took over its administration. The move sparked international debate, but Turkish officials assured that Christian elements would remain protected.

A Symbol of Unity and Continuity

Today, Hagia Sophia remains a functioning mosque, welcoming worshippers and visitors alike. Non-Muslim tourists are permitted entry outside prayer times, with dress codes in place to respect religious decorum.

Hagia Sophia’s dual identity — as a church and a mosque — makes it a rare space where Christianity and Islam coexist within the same architectural narrative. Its grandeur, innovations, and layered heritage continue to inspire awe and dialogue. Whether viewed through the lens of faith, history, or design, the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque stands as a timeless symbol of coexistence, adaptation, and cultural endurance.

References:

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- National Geographic

- Cambridge University Press (Mark & Çakmak)

- Turkish Ministry of Culture

- Encyclopaedia Britannica