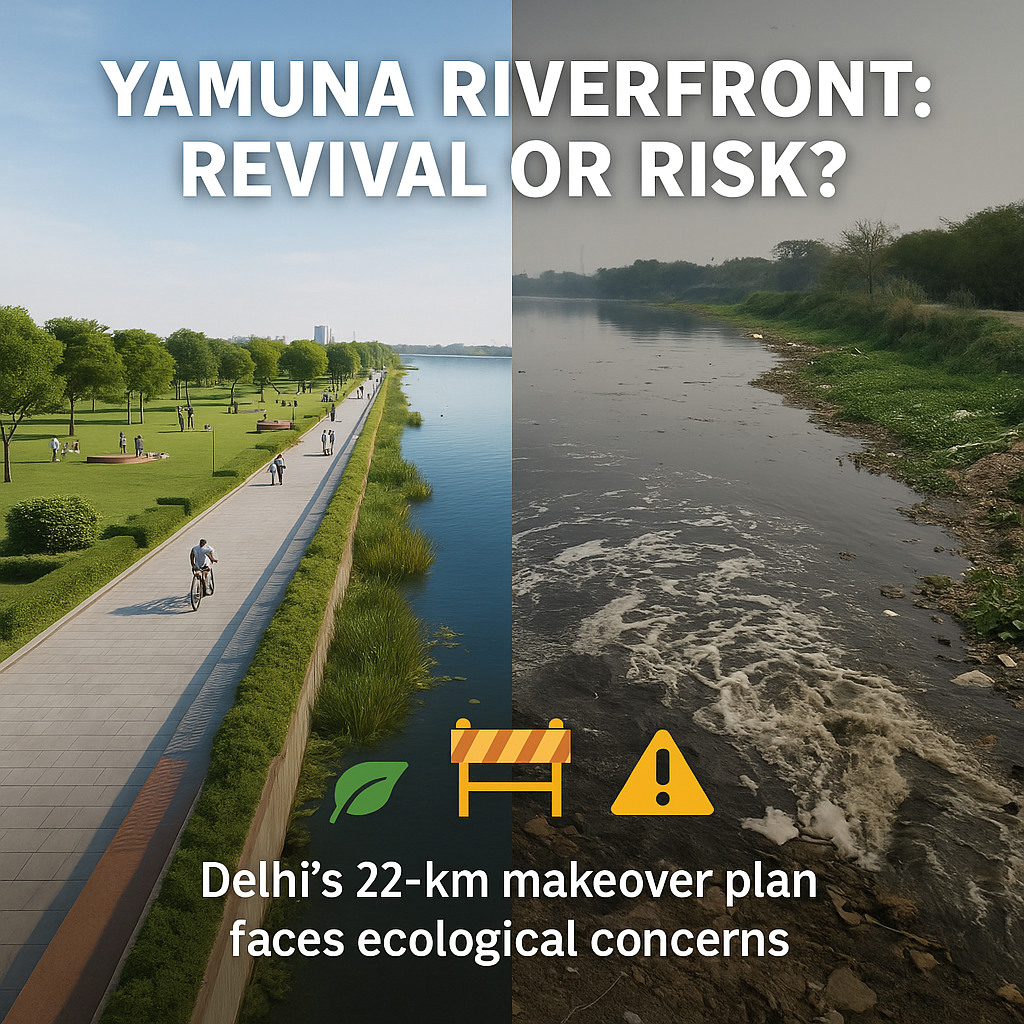

New Delhi: The Yamuna Riverfront River in Delhi is poised for a dramatic transformation. Inspired by Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Riverfront, the Delhi government has unveiled an ambitious 22-kilometre riverfront project stretching from Wazirabad to Okhla. Spearheaded by Chief Minister Rekha Gupta and Lieutenant Governor V.K. Saxena, the plan aims to create vibrant public spaces along the Yamuna—complete with promenades, cycle tracks, parks, plazas, cafes, and biodiversity zones.

However, while cranes move in and wetlands emerge, a chorus of concern is growing among environmentalists and river experts who caution that beautifying a dying river without first reviving it could spell ecological disaster.

A Riverfront Vision in the Making: Yamuna Riverfront

The Delhi Development Authority (DDA), the principal agency executing the plan, is already implementing several floodplain development projects:

- Yamuna Vanasthali (237 ha) – Complete, with recreational wetlands and greenways

- Vasudev Ghat (16 ha) – Features lawns, a 3-km cycling track, and evening Aarti rituals

- Asita East (197 ha) – Nearly complete, opened in 2022 near ITO Bridge

- Yamuna Vatika (200 ha) – 65% complete, includes restored water bodies

- Amrut Biodiversity Park (90 ha) – Fully developed with over 14,500 trees

- Mayur Nature Park (372 ha) – Expected to be the largest nature reserve

- Baansera (263 ha) – A bamboo-themed zone, currently 30% finished

The projects aim to blend ecology and recreation—creating urban spaces that integrate native vegetation, walkways, and eco-tourism facilities.

Ecological Revival: Still a Distant Dream

Despite these developments, the Yamuna continues to rank among the most polluted rivers in India. Often resembling a fetid drain more than a flowing river, it suffers from industrial effluents, untreated sewage, and diminished flow due to upstream dams.

Experts argue that Delhi is repeating the mistakes of the Sabarmati model—one where artificial water flow masks ecological degradation. “Replicating the Sabarmati model could lead to the complete destruction of Yamuna as a river,” warns Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asian Network on Dams, Rivers and People.

Hydrologists and ecologists stress that without natural water flow, intact floodplains, and pollution control, any beautification effort is only a cosmetic solution.

Floodplain: The Heart of the River’s Survival

In 2023, the Yamuna Biodiversity Park offered a glimpse of what could be possible—it absorbed excess floodwaters naturally, highlighting the importance of restoring riparian ecosystems. In contrast, other riverfront parks reportedly require treated sewage to maintain their greenery, indicating ecological imbalance.

Government sources acknowledge this dilemma: “A river can’t be healed without healing its floodplain.”

While DDA has proposed regulatory measures under Master Plan Delhi 2041, including the creation of “O Zones” for river regulation, critics argue that dividing the floodplain into Zone I and Zone II (with differing degrees of protection) may undermine holistic conservation efforts.

The Crossroads: Park for the People or River’s Demise?

The Yamuna riverfront promises urban rejuvenation—but at what cost? The ultimate test for Delhi’s planners lies not in how many cycle tracks are built, but in whether the Yamuna can once again flow clean and free.

Unless the city tackles core issues—sewage treatment, encroachment, and ecological restoration—its riverfront dream risks becoming a monument to lost opportunity rather than urban renewal.

Also Read: Rejuvenating the Yamuna: Can India’s Most Polluted River Be Saved?